MISSOURI, USA: The global war on terror launched by the administration of US President George W. Bush began with Afghanistan in 2001, shortly after 9/11, and expanded into Iraq two years later.

The respective regimes of the Taliban and Saddam Hussein were toppled, the autonomy of the Kurdish region of Iraq was legally recognized, and for a brief moment Afghans and Iraqis enjoyed hitherto unheard-of freedoms. But neither country would end up being saved.

As the Americans finally withdrew from Afghanistan last month, the world watched the Taliban retake the country much more quickly than most people could have imagined. Meanwhile, Iraq increasingly looks like a forgotten, broken land — a playground for militias backed by Iran.

One might conclude that both the Afghan and Iraq wars were nothing more than a colossal waste of blood and treasure. Some commentators in Washington are now suggesting that phrases such as “nation building” and “we will install a new government” should be struck from the lexicon of American policymakers.

Banishing such grandiose policy goals from the American imagination might prove wise, indeed. The ethnic and sectarian divisions in both Afghanistan and Iraq were never something that the US or other Western powers could “fix.”

Installing new governments, holding elections and injecting huge sums of aid money in a short space of time created kleptocracies in both countries, rather than functioning democracies.

An Iraqi man passes in front of a disfigured mural of ousted president Saddam Hussein titled "Saddam, the glory of the Arabs" at an entrance of the former military training camp in Samawa, 270 kms south of Baghdad, 24 February 2004. (File/AFP)

These new democracies lacked a genuine shared national identity that superseded local, tribal, ethnic and sectarian loyalties. And with the overthrow of the previous regimes, they also lost any institutions they might have had to manage themselves. Flush with outside cash, or “aid money,” they quickly became elaborate, and very corrupt, patron-client systems.

Traditionally dominant groups who found themselves demoted within, and even excluded from, the new corrupt, neo-patrimonial system — the Pashtuns in Afghanistan and Sunni Arabs in Iraq — led insurgencies against the new states.

These insurgencies made the productive use of aid money — to build schools, electricity grids and bridges, for example, or sustain agriculture — that much more difficult and uncertain. Elected leaders instead used their time in office to enrich themselves and members of their clans or sects.

Two US soldiers from the 1st Brigade of 4th Infantry Division show the hole where toppled dictator Saddam Hussein was captured in Ad Dawr, near his home town of Tikrit, 180 kms (110 miles) north from Baghdad, 15 December 2003. (File/AFP)

Whereas the Taliban eventually were able to use the resulting popular frustration (as well as Afghanistan’s very rough terrain and proximity to backers in Pakistan) to take back power 20 years after their overthrow, Sunni Arabs in Iraq will probably never rule the country like they did before. Since Shiites and Kurds make up about 80 percent of Iraq’s population, that is probably a good thing.

The more problematic result of regime change in Iraq is the overwhelming Iranian influence in the country now. If Daesh represented the last Sunni Arab effort to regain power in Iraq, it also provided Iran and Iraqi Shiites with the impetus to form unaccountable Shiite militias, which now run rampant across the Arab parts of the country.

Smoke billows from an explosion in the presidential compound in Baghdad 27 March 2003 following a US-British air raid. (File/AFP)

Just like in Lebanon and Yemen (other countries now largely run by Iran’s proxy Shiite militias), the Iraqi state now looks like a hollow shell, unable to provide services for its people and run by the AK-47-toting Partisans of Ali who man checkpoints all across the country.

The predominantly Shiite Popular Mobilization Forces seem impossible to dislodge, especially having won legal recognition and a salary from the state — even though Iraq’s elected government does not control them.

In the Kurdish north of Iraq, the two main ruling families have done a better job of building a decent, functioning administration. Yet they, too, hold onto their own family-run armed forces, the Peshmerga, and are responsible for a fair amount of corruption.

Could things have been different? What if the Americans had not stayed on to occupy Afghanistan and Iraq after toppling the Taliban and Saddam?

Both of the wars initially went very well for US forces. In a matter of weeks, and with next to no casualties, the Americans removed both the Taliban and Saddam’s Baathists from power.

What if, immediately after these swift victories, the Americans had brought leaders from all the relevant communities to the negotiating table and told them: “We’re leaving in two weeks — work it out among yourselves in a decent way or we will be back?”

In Afghanistan, the result would probably not look so different. The Taliban would have retaken power in short order, although perhaps not in the north where Abdul Rashid Dostum’s Northern Alliance could have made some gains.

Ironically, the Taliban now control more of Afghanistan than they did 20 years ago at the time of the 9/11 attacks. At least in a “quick departure” scenario after the early successes in 2001, the US and its allies would not have squandered so many lives and so much money in a futile “nation-building” effort.

In Iraq, a swift coalition departure after toppling Saddam in 2003 would probably have led to an equally bad result. In response to Kurdish gains — the Kurds were the most organized and well-armed Iraqi group immediately after the fall of Saddam’s regime — Turkey would probably have invaded Iraq, much as it did Syria in 2019 and 2020.

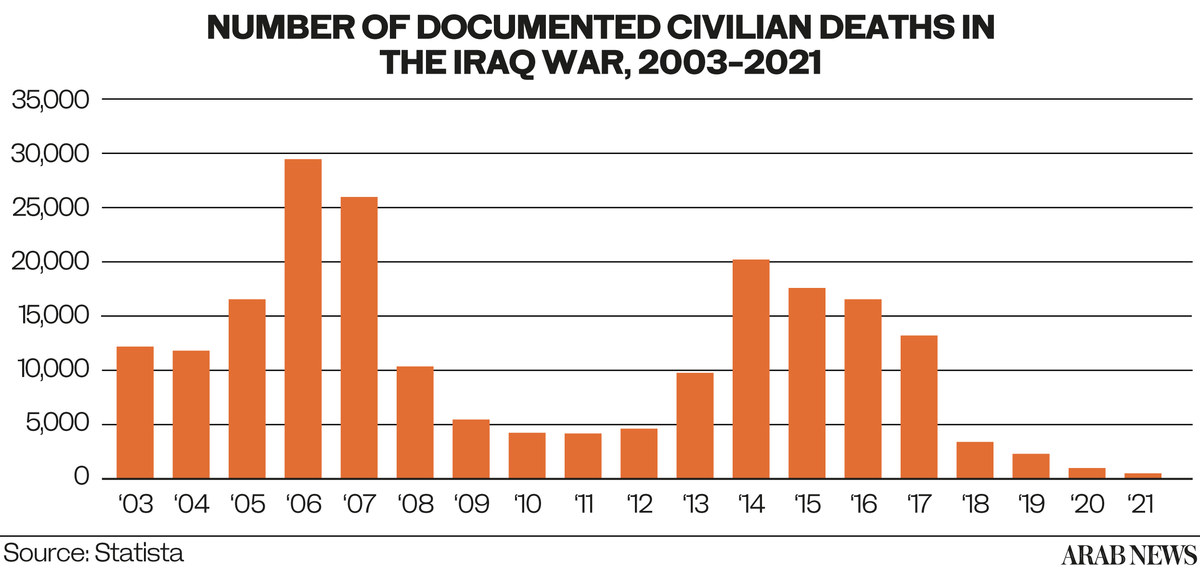

Threats against Shiite Iraqis by Sunni Arab extremists and former Baathists would have led to an Iranian intervention — again, much like in Syria — and the bloodletting would probably have been worse than it was in 2006 or 2014. Decades of Baathist repression in Iraq had created too much friction between the communities, which no amount of US involvement could have rectified.

Two US soldiers from the 1st battalion, 22nd Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division secure the parameters during a foot-patrol along a street of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's hometown Tikrit, Baghdad, 27 December 2003. (File/AFP)

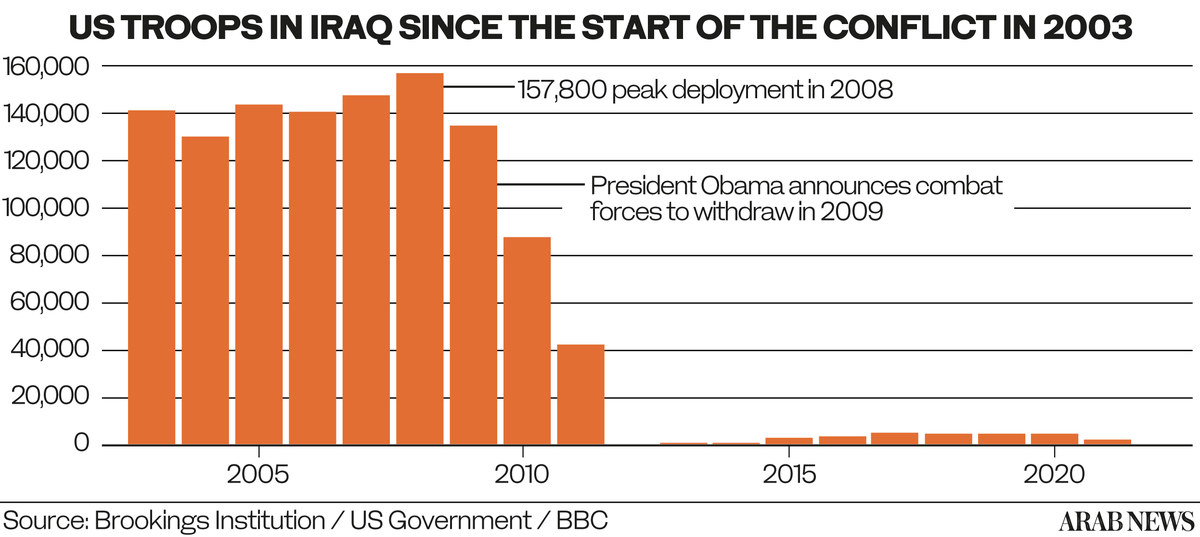

Alternatively, what if after 9/11 the US had not invaded Afghanistan or Iraq at all? At the very least, more than 7,000 young American soldiers would still be alive today, a great many more would not have been wounded, and the US treasury would be in much better shape than it is.

Some heavy-duty bombing raids on Al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan might have quenched the American thirst for justice, or vengeance, following 9/11, although it probably would not have been enough to satisfy many. Al-Qaeda might have remained a much stronger force than it is today.

Iraq presented a more complex problem, as the country was on the verge of successfully beating the sanctions imposed on it in the 1990s, along with other Western attempts to contain Saddam.

US soldiers check Iraqis men in the southern Iraqi city Nassiriyah 17 December 2003 before they enter the Talil base in order to deposit a complaint against the US army for material damage caused by coalition forces during their intervention. (File/AFP)

One could easily imagine Saddam exploiting such a political victory in the same way Gamal Abdel Nasser used his military defeat in the 1956 Suez Crisis. Although Nasser lost the war, the political victory he gained from forcing the British, French and Israelis to withdraw made him a hero throughout the Arab world and beyond.

A similarly reinvigorated Saddam might have restarted his nuclear program and gone on to cause untold trouble for his Gulf neighbors, his own people (massacring a great many as he did before) and for the region as a whole.

In the end, not even 20 years of hindsight can offer 20/20 vision as we look back at the events that followed 9/11. Sometimes there are no good choices, only bad ones and less-bad ones.

Twenty years of “nation building” in Afghanistan was probably a bad choice. Overthrowing Saddam and trying to remake Iraq, on the other hand, might have been the less bad choice — but still a pretty bad option nonetheless.

* David Romano is Thomas G. Strong Professor of Middle East Politics at Missouri State University