DUBAI: Chicago-based artist Michael Rakowitz has a confession to make, right off the bat: He has never been to Iraq. This might come as a surprise, since the Iraqi-American is known for tirelessly devoting himself for over a decade to shedding light on the destruction and looting of Iraq’s indigenous cultural heritage, starting from the 2003 US occupation to the rise of Daesh, as well as extractions carried out by museums in the West.

However, his memories — especially those of hearing conversations in Arabic between his grandmother and mother while growing up in New York — are steeped in Iraqi history. “I heard the good things and the wondrous things,” he tells Arab News.

Rakowitz’s family is of the Jewish faith. In 1941, a violent pogrom, known as Farhud, aimed at Jews, took place in Baghdad, which was then a multicultural city. Many of them eventually fled their homeland.

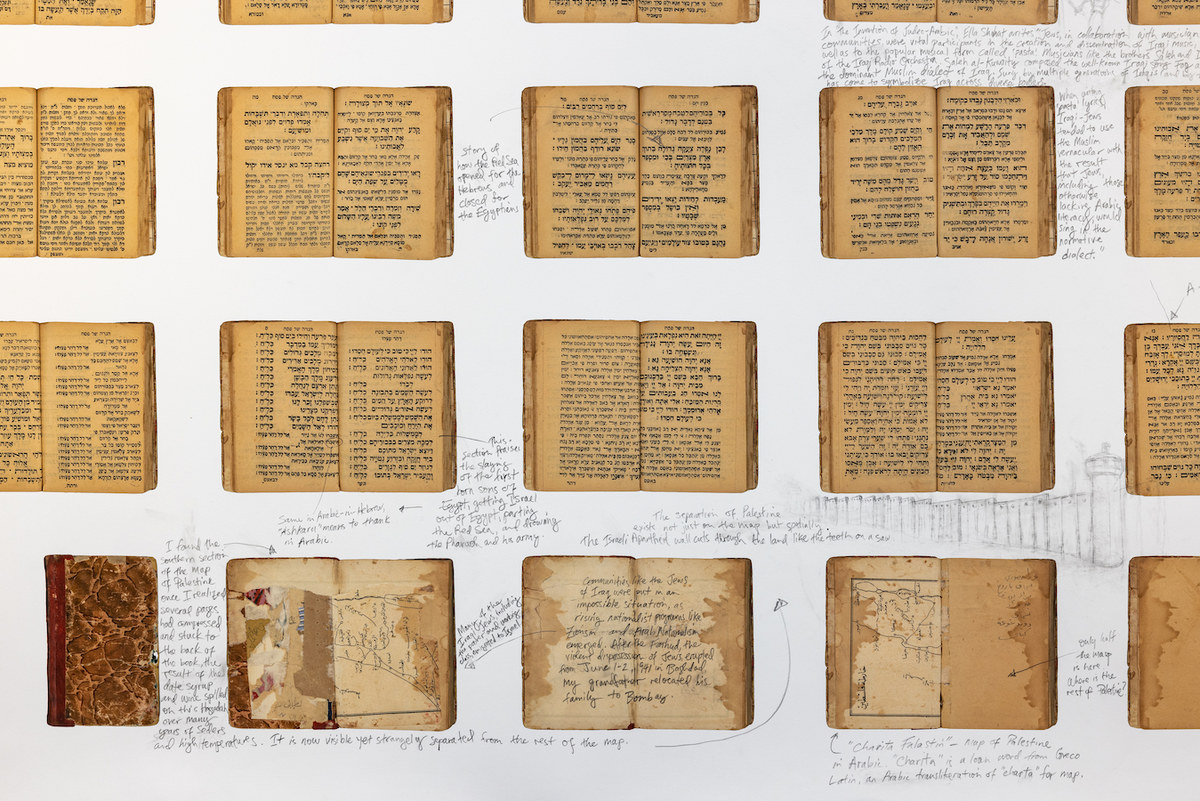

Michael Rakowitz, Charita Baghdad (detail), 2020, Graphite on archival digital print, 1.1 × 4.57 m. (Photo credit: Anna Shtraus)

“My grandparents and their children were suddenly and abruptly separated from that place. When I was growing up on Long Island, they created conditions where we were all surrounded by things that were like portals to that place,” Rakowitz says. “They were their memories of daily life there and what it meant to them. They passed them on to my mother, who was very young when she arrived to the States.”

His family history is partly explored — through a long, annotated chart dotted with pencil notes and pages from the Jewish Haggadah prayer book — in Rakowitz’s solo show at Green Art Gallery in Dubai, which runs until Nov 23. Entitled “The invisible enemy should not exist,” the exhibit also showcases Rakowitz’s ongoing installation project, which began in 2007, addressing the looting of thousands of precious artifacts from the National Museum of Iraq following the invasion. He describes this work as “a ghost to remind.”

With the help of his assistants, Rakowitz “reappears” the looted artifacts by creating detailed, papier-mâché relief-like sculptures, made of fragments of Arabic and English newspapers and Middle Eastern food packaging from grocery stores.

The resulting sculptures are intentionally colorful — “breathing life” into the artifacts. “The sheer number of what’s still missing at the museum will outlive me and my studio,” Rakowitz says.

“We’ve made about 800 of those objects; it’s taken 16 years to do that,” he continues. “In reappearing all of these things, we understand how much is missing. For me, those objects are never not tied to people. When the world saw the looting of the museum, there was an agreement that this was not simply a localized Iraqi loss. It was a loss for all of us.”

The curious name of the show is a translation of “Aj ibur shapu” — the name of the processional way that ran through the iconic blue Ishtar Gate of Babylon. “When I read that it meant ‘The invisible enemy should not exist,’ I thought that was the coolest name for a street that I’d ever heard,” says Rakowitz. “It was so mysterious, but it also makes you think about other things, especially during a time of war, in a place like Iraq that is under assault. I thought that was a perfect title for a project like this, using some of the poetics of ancient Mesopotamia as a way of speaking about the now.”

A newer branch of Rakowitz’s project focuses on a historical site near Mosul: the Northwest Palace of Kalhu, from which hundreds of panels (now reappeared by Rakowitz) have been taken by major museums over the years, and which was mostly destroyed by Daesh in 2015.

Rakowitz uses very specific terminology when it comes to describing his practice. Observers could analyze it as a symbolic form of preserving, remembering, or informing. “There is an opportunity to reappear, but it’s not a reconstruction,” he explains. “I used to reconstruct but then, when the 3D printing rage started to happen about 10 years ago, I started to think more critically about the fact that these are ghosts that I’m making.

“I’m making them out of very vulnerable material. So, it’s a reappearance of something that is disappeared that will disappear again,” he continues. “It’s crucial that it should not necessarily be something that hides the scar of the fact that something has happened. Even in the midst of making things present again, there is a loss that can’t be recouped.”