In London’s Brunei Gallery two Egyptian peasants sat, diligently weaving colored threads into a small tapestry. The threads were being transformed by their fingertips into a scene from the Egyptian countryside — a palm tree and peasants. Visitors to the exhibition gathered around the women, marveling at the simple yet beautiful shapes they were creating. One of the visitors — a woman — began to speak enthusiastically to one of the weavers.

The weaver whose name is Sabah does not speak English so she looked at me and asked me to translate. I told her. “The woman said she went to the art center where you work in Cairo and she wants to go back again and hopes to see you there.

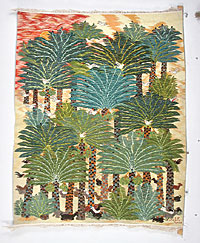

With a smile, Sabah said to the woman, “You will honor us and bring light into our center.” Sabah pointed to her work proudly and said, “I have other pieces in this exhibition, one of them showing a flowering tree in the spring.” The other weaver, Reda, continued to work and the visitors to the exhibition watched the tapestry she was creating.

The exhibition — “Egyptian Landscapes: 50 Years of Tapestry Weaving at the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center, Cairo” — opened in the Brunei Gallery at the School of Oriental and African Studies on Jan. 19 and runs until March 17. On display is the work of weavers from the Wassef Center; the work ranges from items done fifty years ago to those done very recently.

Ramses Wessa Wassef, the founder of the center, was an architect who studied in France and had dreams of developing the authentic lines of Egyptian architecture.

After his return to Cairo, he was working in a school and, as he believed that each person had a creative talent within, decided that he would try to discover and nurture that talent within some of the schoolchildren. Thus, he started a little workshop where he taught the children how to weave and encouraged them to use their imagination and weave scenes from nature which were familiar to them. To ensure that the project continued, he built a small art center outside Cairo in a small village called Al-Harranyia and from there began what developed over the next 50 years into a full-blown business.

“He chose tapestry because it requires patience, time and perseverance,” said Ikram Noshi, Wassef’s son-in-law. “It also gives the children time to mix what they see around them in nature with what is in their personal imaginations.” Noshi pointed out that from the beginning, each child was encouraged to express his or her own individuality. They were not allowed to copy each other’s work and Wassef made them feel proud of every idea they had. Noshi continued, “Wassef believed that the hidden talents needed time and patience to mature. Some of those children might need more time than others and he gave them that time. In those days, the children received a monthly allowance, health care and whenever one of their pieces was sold, they received about one-third of the selling price.

The themes chosen by the artists have of course changed over the years. The early works showed the simple nature and life of traditional Egyptian villages — a donkey market, a fight in a coffee shop or a field of sunflowers. “Now,” said Susan, the daughter of Ramses Wassef, “you see carpets with houses and satellite dishes on them, tourists and cameras: Things that never showed up in the early work.” Susan joined her father, mother and sister at the center after she finished school. She was in charge of the second generation of weavers and she introduced pottery and ceramics.

She said proudly that her father’s work would also be remembered because he loved the people around him and he had endless patience. “When he died in 1974, some of the old weavers said to me ‘We used to look at him and feel that we are looking into a mirror; he knew what was inside us and helped us to get it out onto a tapestry.’” Sabah and Reda were asked how they got their ideas and how they started work on a new project. Sabah said, “Whenever I get an idea, I go to Madam Susan and tell her what’s on my mind and she always encourages me to go ahead.” The scenes in the exhibition range from Egyptian countryside to scenes from cities, such as a scene from the zoo and another one of a crowded street in Cairo. Susan explained, “We usually take the children to the seaside or into Cairo so that they can see things and places that will inspire them and enrich their imaginations.” On one side of the exhibit, I saw a collection of tapestries that were different in themes and colors. Susan explained that they were done by British children who visited the last exhibition and were so impressed by what the Egyptian children had done that they sat down and began weaving their own carpets and tapestries.” With such a legacy, Susan and her sister have continued the work on the center that has become a landmark on the Egyptian art scene.

It has done a number of international exhibitions and has always attracted a clientele who appreciated the talents and artistic abilities of the Al-Harraniya weavers.