THE real value of history lies in what it tells us about the world we live in. When we are born, we arrive in a readymade world. Only gradually do we extend our awareness of it beyond the confines of our immediate family and culture. Over time we come to appreciate the continuity of our own culture and, through education and communication, perhaps begin to understand the continuity of others.

Thus, when a piece of the Kingdom’s history lies virtually unknown in a couple of metal cans in a small office in central Jeddah, it should be a cause for great concern. The historical artifact is a few halalas worth of celluloid film stock; what it contains as history is priceless.

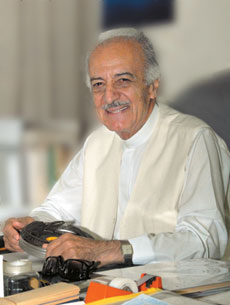

Safouh Naamani works still from an office in central Jeddah where he has a remarkable collection of photographs and movies of his work dating back to the mid 1950s.

He is a wiry and very lively octogenarian with an artist’s eye and a formidable memory for detail. From an early age he rarely was without sketchbook and pencil and with his natural eye for an image developed into a skilled graphic artist with an inclination towards engineering drawing. It was when he encountered his first movie camera as a boy — brought to his home in Lebanon by a cousin — that his real passion began.

“Amateurs of the 1930s those days were using 9.5 mm movie cameras,” he recalled. “It fascinated me very much to see the images projected on the screen at home, but also the mechanism of the camera and the projector.”

This encouraged him even at a young age to learn the technology of film cameras as well as their product.

“When I understood how the cameras worked, it was a natural progression to wanting to make a film. I had ‘the eye’ and I was fascinated with others work, so I tried it myself.”

It was a combination of artistry and story that attracted young Naamani to the documentary format. Fed on a newsreel of the Egyptian film industry a song of Um Kulthoum about the Pilgrimage was the sound track, which, he thought, deprived the subject of its sanctity, Naamani quickly decided to adopt a different approach.

“I wanted the movie to tell the story, with no such music,” he said, “thus sanctifying the subject, the Pilgrimage to Makkah, the Fifth Pillar of Islam”. Over half a century ago that was not easy even for professionals.

The fledgling documentary maker took up producing and shooting films as a hobby.

“To produce you have to learn so much,” he said. “What brought things together for me was my cousin’s Encyclopedia Britannica. He bought all 24 volumes — in 1933.”

Although he read avidly, Naamani’s natural talents resulted in a career inclining towards engineering. The engineering background later helped considerably in following the processes of the film industry.

“I came to Saudi Arabia in 1951,” he said. “I made many friends whom I am proud to have until this date.”

During 1952 and 1953 Haj, there were several attempts of shooting some film scenes in Makkah, the Grand Mosque and the pilgrimage sites, which included rare footage for later use. But in 1954 a fire tore through his studio and wiped all of Naamani’s exposed films, except for one can of film from 1952 dug up from the rubble of the fire. This tragedy did not stop nor discourage this filmmaker.

“Ironically, the films exposed at that very time eventually got destroyed at a later date by the Vinegar Syndrome, a common virus in the film industry,” he said.

Cellulose nitrate film stock was in commercial use through the early 1950s, when it was replaced by cellulose acetate plastic “safety film.” Nitrate degradation is a slow chemical process that occurs because of two factors: The nature of cellulose nitrate plastic itself and the way that the film is stored. As nitrate film decays, it can become highly flammable at relatively low temperatures. A small portion of the original film of 1952, though badly damaged, still exists.

As the pilgrimage of 1954 drew nearer, he continued the planed filming activity. Several dignitaries came to perform the Haj, he was ready and filmed the coverage at various locations with outstanding results that shows Makkah in glorious detail. “This was the basic for me” he said.

In 1955 Naamani, then 29, left for the United States to go back to school for his higher education and film making. “I was one of the oldest students; it was very difficult for me.” It was to be eight years before Naamani returned to film making activity, to continue his objective.

“This was the first time the Haj had been filmed as a story and documentary,” he said. Up until then, only news-clips and newsreel scenes existed, filmed mostly by Egyptian crews.

Naamani had performed Haj twelve times and had collected images and scenes in his mind, but had not written a script. He obtained the necessary permits and was commissioned to start production.

So armed with his camera, the barest of shooting notes and a gritty determination, Naamani filmed the 1963 Haj from landing at Jeddah ports — both Sea and Air — the mass migration to Makkah and Mina to the standing on Mount Arafat.

“This was the very first color movie of Makkah and the Haj. “It is the definitive film. I had to work from scratch.”

After cutting and editing, the film had to be narrated. The script was written by a friend of his who, he said, worked from his own heart producing an excellent story. The script was corrected from any mistakes, especially religious content. “Later I had a stroke of luck,” he said,” an experienced narrator, Isa Sabbagh.”

“He was amazing,” said Naamani. “This guy, Isa Sabbagh, a Palestinian Christian, was very famous. During the war he announced from London and earned the soubriquet the “Golden Voice of the Arabs”. He knew his profession very well. He knew the Qur’an and understood all Islamic background.

Sabbagh was delighted with the script and recorded the voiceover in the living room of Naamani’s home. This was film making at it’s rawest but, Naamani said, given care and reasonable equipment, a quality job will result.

The pair then sat for a day and while Sabbagh translated the script into English, Naamani typed it up.

Recording voice for film is usually done while the voice artist watches the film from a soundproof recording booth. In this case, that was simply not possible, so it was recorded straight from the script; Sabbagh judged the timing from the script. “The man was a true professional; and the whole lot was done in one take — that was really incredible.”

To see the finished film is to enter a time warp and live the Haj of half a century ago. Cut into the film are shots of the Ka’aba and Grand Mosque from the 1954 footage. The muted slightly pastel colors of the film and the rich mellifluous tones of Sabbagh’s slightly declamatory style of delivery place the film firmly in the middle of the last century.

Coaches, very similar to the yellow school buses of today, thread their way through pedestrians streaming towards Makkah. Camels, complete with “hawdaj” — a box like construction with long side struts — perched on top, weave unsteadily with an aristocratic air through the throng. The scenes are of a happy chaos, hundreds of thousands of people with one peaceful purpose.

It is history being made and a marker for the modern generations of Muslims around the world to point to and understand the continuity of their culture. Not just Muslims; the fact it was narrated by a Christian in itself speaks volumes about the historical value of cross cultural interaction and cooperation.

Sadly, this remarkable film was never distributed.

The stills and records of the film and all Naamani’s photography are stored in crisp acid free slips and meticulously labeled. It is part of the nation’s history, but few have ever had the chance to see it; fewer still even know of its existence.

Philosophically, Naamani carried on making films and building his business over a long and productive life. He still however, rightly regards the Haj film as something very special.

As I was leaving he held my hand for some moments after shaking it. “Do you know,” he said rather wistfully, “I have never seen it on a big screen?”