The fact that we crave live news and enjoy good articles and eBooks should not affect our love for physical books. Histories of events are now being written ever so rapidly, and often, with a lack of perspective. The minute-by-minute Web-based reporting enables to read instantly what journalists have written, but time and space are needed for historians to correct journalists’ early mistakes and get the story right.

Bestseller lists, on the other hand, feature regularly serious history. “These are books that even technologically savvy consumers prefer to read in paper, so they feel the weight of research on each page,” says Frank Partnoy, author of “The Match King.” Furthermore, as eBooks get shorter and are published faster, differences in form and value will become evident.

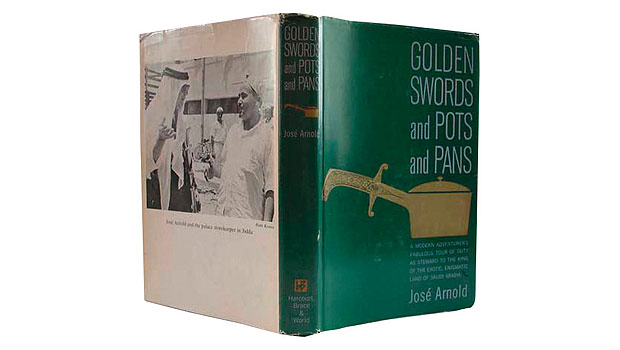

All this has triggered a renewed interest in books whose release might have gone unnoticed but that today have real documentary value. This is the case of “Golden Swords and Pots and Pans” (Harcourt, Brace & World 1963) by Jose Arnold, which describes Saudi Arabia in the 1950s. I was recently delighted to find a used copy of this book, which is out of print.

There were not many foreigners in the Kingdom during the 1950s, and few books were written about that period. What sets this book apart is that the author unexpectedly became Chief Steward to King Saud and wrote from a unique perspective, an entertaining account full of humor, about a way of life that no longer exists.

Arnold, an American originally born in Switzerland, was looking for a quiet job in the desert when he accepted, in 1947, a position with Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) as supervisor of the company’s restaurant at Dahran. In 1950, he was named camp boss for a crew of workmen who were building a section of the railroad between the capital in Riyadh and the Aramco headquarters in Dhahran. His life was about to change in the most unexpected manner.

Suddenly, one day, Arnold received a message on the radio transmitter-receiver — “the only link with anything resembling civilization” — that the crown prince and his entourage would stop at the camp for lunch on their way back to Riyadh. Arnold had less than two days to make all the preparations.

The dining facility was an air-conditioned railroad car with a row of card tables down the center. “I put bed sheets over the card tables…To reduce the stark, dreary dinginess of the surroundings, I captured a passing tumbleweed, propped it up in front of the Crown’s Prince place setting, fashioned some flimsy rosettes out of bits of colored napkins, attached them to the branches of the weed, and stood back lest my cigarette turn this makeshift mirage into a flaming fury,” writes Arnold.

Prince Saud bin Abdul Aziz, then crown prince, not only enjoyed lunch (particularly the “Chicken Cacciatore”), but also the flowers. “From what country did you import those flowers?” he asked Arnold who never realized this humble arrangement would attract so much attention.

A few days later, the crown prince requested Aramco to send Arnold to his Al-Nasariyah palace in Riyadh to show his cooks how to prepare the same food that was served when he visited the construction camp. At the end of another successful meal, Prince Saud wanted Arnold to continue cooking for him. Arnold declined the offer because although he prepared a few dishes, he was not a professional cook and already had a job he was responsible for.

However, when Crown Prince Saud succeeded to the throne in 1953, he asked Aramco to take over the responsibility for the administration functions of his palaces. Arnold, in view of his previous successful dealings with the future king, was named palace steward. For the next five years, he was solely responsible for the annual budget, covering expenses for operating the kitchens in the 10 palaces of King Saud that had been built or were under construction.

In the fall of 1956, the new Al-Nasariyah Palace in Riyadh was nearing completion, and the king had ordered a gala banquet for its inauguration but:

“As in Jidda, the contractors were concerned only with the sections of the palace that would be shown to King Saud during the official opening ceremony. And when the banquet hall, the majlis and the king’s private offices, as well as the impressive façade of the reception palace were virtually finished, the kitchen was ready to prepare only a one-course meal of mud pies,” says Arnold.

Just one week away from the gala banquet, the stairway from the kitchen to the banquet hall was still only a pencil mark on the drawing plan. Exasperated, and infuriated at the general lack of concern, Arnold walked directly to the throne room, opened the door without waiting for the required protocol, and burst into the midst of King Saud’s daily audience.

King Saud became upset when he heard about the condition of the kitchen. “He instructed an aide to summon all of the Al-Nasariyah contractors at once. Then he thanked me for having brought the matter to him and, dismissing me said, ‘plan our finest banquet; the work will be finished,’” writes Arnold.

The banquet was another huge success. Arnold played an instrumental role and he followed King Saud on all his major trips inside as well as outside the Kingdom. He was part of the delegation that accompanied the King on his first official visit to the United States. President Eisenhower, who had extended the invitation to the Saudi monarch, “pointedly came to the airport to greet his guest in Washington, an honor he had accorded no other ruler or statesman in four years,” says Arnold.

Of all the state visits, the most memorable, according to Arnold was that of the late King Faisal of Iraq and his uncle the late Crown Prince Abdul Illah. King Faisal had come for a second visit to Saudi Arabia during the first week of December 1957. The 21-year-old Iraqi ruler, who was only five feet two inches in height, presented a sharp contrast to the tall King Saud. King Faisal and Crown Prince Abdul Illah displayed an easy camaraderie and “the apparent absence of protocol among them were a refreshing change in the palace,” writes Arnold who was delighted to receive an invitation by King Faisal to go to Baghdad and be a guest at the palace.

A few months later, en route to Switzerland for a two-week vacation, the Dahran to Zurich flight was broken by a refueling stop at Baghdad. Arnold decided at the last moment not to accept the invitation extended by King Faisal. Three days later, the front page of the Zurich newspaper mentioned the assassination of King Faisal and Crown Prince Abdul Illah. It was reported that the Swiss housekeeper had escaped without injury. “I wondered if I would have been so fortunate,” writes Arnold.

“Golden Swords and Pots and Pans” is an invitation to travel, a journey back in time, during the 1950s when few expatriates lived in Saudi Arabia and the world knew very little about this ancient land. The author gives a feisty account of the five eventful years he spent with King Saud. His attention to detail, and a formidable sense of humor, will please anyone interested in the Kingdom’s modern history.