PARIS: In May 1987, the Cairo-born French-Italian singer Dalida — one of non-English-language-music’s biggest-ever stars — took her own life. Her 54 years had been filled with both great success and great tragedy. Three of her partners had previously committed suicide, and Dalida had attempted to take her own life in 1967 after the suicide of her lover, the Italian singer and actor Luigi Tenco.

Despite the trauma of her personal life, though, her career was a story of almost-unbroken achievement. She packed out venues across the world, her songs (sung in nine languages) sold in huge numbers, and she was even a hit on the silver screen in films including legendary Egyptian director Youssef Chahine’s 1986 release “The Sixth Day.”

In France, where she lived most of her adult life, she was an undisputed superstar — a poll in 1988 published in Le Monde ranked Dalida second, after General de Gaulle, among personalities who had the greatest impact on French society. She continues to influence pop-culture today, with many of her hits being remixed as dance numbers.

Here, her younger brother Orlando — with whom she co-founded their own record label in 1970, in order to give her more control over her career — shares his memories of his legendary sister with Arab News.

Dalida in Rome in the 1950s. (Getty Images)

Tell us about growing up with Dalida. What was she like as a kid?

Dalida — who was called Iolanda at the time — grew up with my brother and me, the youngest. My name was Bruno, but when I arrived in France and started my career, I was given the name Orlando. We grew up with the same education, in the same neighborhood, the same atmosphere, and yet we were totally different. If my brother and I had a very joyful, very happy childhood, this was not the case for Dalida. She was a little sick when she was little (she had an eye infection and underwent several operations) and, growing up, she always had this desire to go elsewhere — a desire to know the world, to rise, to learn, to be cultivated. She always had this goal: ‘One day, you will see who I am.’ She wanted to ‘become someone.’ She built herself with this goal in mind.

How connected did she feel to Egypt?

We lived there; we were born there. We bathed in its atmosphere. Egypt, at the time, was a country of unique sweetness, with a cultural mix that was extraordinary — all these languages, all these cultures, all these religions, all these people who rubbed shoulders, who were dating… There was no discomfort, no aggression. There was such a sweetness of life. We had a beautiful childhood in Egypt. Dalida adored Egypt, she always remained faithful to it, and, moreover, after a few years, she began to sing in Egyptian.

French actor Jacques Charrier poses with his wife, actress Brigitte Bardot (right) and Dalida at the opening of Dalida's show 'Jukebox' in 1959. (Getty Images)

What made your sister such a special talent?

This particular talent, we can’t explain it. She had many talents, which were enriched by her voice — this tone which belonged only to her, indefinable; this warmth of the voice, this burst of sunshine. Above all, I think her voice was born from the Mediterranean, it’s a voice tinged with the sun, from the Orient. And the fact that she was of Italian origin and sings in French meant that she had a peculiar accent. Since 1955, this unique voice and the personality that went with it have taken over the world. Dalida has created immortal titles in all languages. To talk about the Middle East, “Helwa Ya Baladi,” for example, has become an anthem for the whole Arab world, and “Salma Ya Salama” too. The hundreds of songs by Dalida, all different, make her unique, because everyone finds something that touches them, a slice of life or the presence of Dalida. She knew how to do everything. She passed with truly astonishing ease from a song like “Je suis Malade” or “Avec Le Temps” to songs like “Gigi L’Amoroso” or “Salma Ya Salama” or to disco. Perhaps thanks to her place of birth and this plural culture, which remained in her memory and accompanied her during her adolescence, she had the chance and the power to sing in all languages. She drew on this mix and it made her career. Dalida will remain unique.

What do you remember about her sudden success? How did it affect her? And you?

I was the witness to her story, and I became the witness to her memory. Dalida and I were accomplices — fans of theater, cinema and song. And I always encouraged her even though I was younger than her. I always accompanied her on her journey — her desires, her dream. I was always her confidant, even when she left for Paris. When I arrived in the capital in my turn, I sang a little too, but after five years I joined the adventure by her side and I never betrayed her — I served her and I keep doing it. So it was a career that we lived together, and I was a spectator, an admirer and also, later, her producer. In 1966, I became her artistic director and in 1970, we founded our own business. Even today, I take care of her as if she was still here. Dalida made me her universal legatee because she knew that I would continue to defend her memory and her interests, and that’s what I am doing.

Dalida and her husband Lucien Morisse in Paris, March 1961. (Getty Images)

When did you first notice that her depression was getting worse? Was it something she struggled with throughout her life?

She used to say, “I succeeded in my professional life, but in my personal life, I did not succeed.” Why? Because she gave everything to her job, to her audience. She wanted to be Dalida, so she became Dalida. She did everything for Dalida and put aside her private life, which suffered as a result. This is the reason why she could not keep the men in her life, because after a while the men saw Dalida in front of them, not Iolanda. She always put her job first, and that’s why she found herself alone. It couldn’t last.

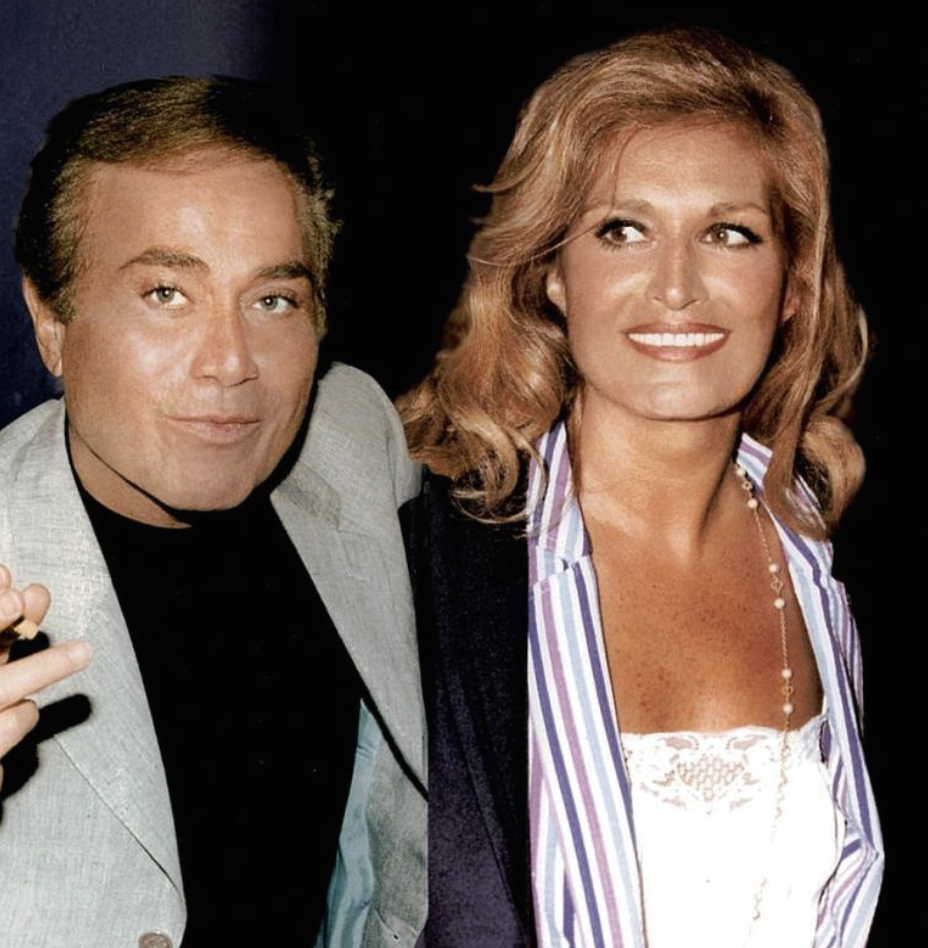

Dalida (right) with her brother Orlando. (Supplied)

Towards the end, she realized that she was alone, childless and without a companion by her side. She began to understand that giving everything for her career — even if it was what she had wanted — had taken away her life as a woman, a wife and a mother. And, little by little, all this led her to have dark thoughts, made her depressed. But despite the dramas, she also had a life full of joy, satisfaction and happiness.

She experienced this terrible tragedy in her life of having three partners who committed suicide. These are things that you can’t explain. After a while she had had enough, maybe she thought she had done everything, and had everything. I don’t think Dalida wanted time to do its work either; she wanted to escape from time. She wanted to leave in full glory and in full beauty.

What do you think she was most proud of?

Dalida was not proud. Despite her status as an international star — an icon even today — she was always a humble woman. She never thought she had ‘succeeded,’ so she kept it simple, knowing well who she was. It was Iolanda who built Dalida — this blonde international star — but also this timeless Dalida.

A shot of Dalida taken in 1955. (Getty Images)

What kind of a cultural legacy do you think she left?

Dalida is one of those rare artists who had a passionate connection with her audience. People loved Dalida passionately, even new generations. Today, people who weren’t even born when she left us love her and listen to her songs. In Montmartre, the bust on Place Dalida, installed in 1997 following a decision by the mayor of Paris at the time, Bertrand Delanoë, has become a cult place. Statistics show that in Montmartre the two most visited monuments by tourists from all over the world are the Sacré-Coeur and Place Dalida. And now there’s even a tour that starts at Dalida’s house on Rue Orchampt, goes to her final resting place in Montmartre cemetery, and then back to Place Dalida where her statue is, which tourists come to touch like a lucky charm.