BAGHDAD: An old adage about Arabic books claims that “Cairo writes, Beirut prints and Baghdad reads.” While this might not entirely be the case today, the last part of the famous phrase still holds true — Iraqis love to read.

Buying, reading and discussing books have long been a crucial part of Iraqi intellectual life that endures to this day, notwithstanding the country’s political ups and downs.

“Books allow us to escape,” Fatimah Jihad, foreign rights manager for Al-Mada Group for Media, Culture and Art, told Arab News. “No matter what happens in the country, there is a great desire to keep the culture of books and literature alive.”

A group of Iraqi children get an early initiation on reading during a book fair in Baghdad. (Supplied)

That is not to say that there have not been great challenges, however.

“Because of the wars, armed militias and the fighting inside Iraq, literature and education have taken a back seat, with people not as keen to educate themselves and to gain knowledge as they used to be,” Aqeel Al-Khrayfawee, an Iraqi archaeological researcher and academic, told Arab News.

“Due to lack of support from the government, the selling, buying and even writing of books has decreased.”

Literature and education have taken a back seat in Iraq as a result of the wars that have visited the country in the past two decades. (Supplied)

However, a number of mostly privately organized initiatives over the past decade across Iraq have been trying to revive this crucial part of Iraqi heritage at a time when traditional bookstores all around the world are increasingly under threat.

At the end of last year, Al-Saqi Books, which was London’s first Arabic bookstore, closed its doors after 44 years of operation.

“It’s been incredible but we have just had to face the facts and realities of the situation: There were just a few too many challenges,” Lynn Gaspard, the daughter of one of Al-Saqi’s two founders, told Arab News in December.

Lynn Gaspard: There were just a few too many challenges. (Supplied)

That same month, thousands of Iraqis and foreigners flocked to the famed Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad. Named after the Abbassid-era poet Abu Al-Tayeb Al-Mutanabbi, the street has long been renowned for its booksellers, coffee shops and intellectual scene.

The street, which still bears the scars of the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, and a car bomb attack in 2007 that killed 30 people and wounded 60, reopened in December 2021 after it was renovated by the Iraqi Private Banks League.

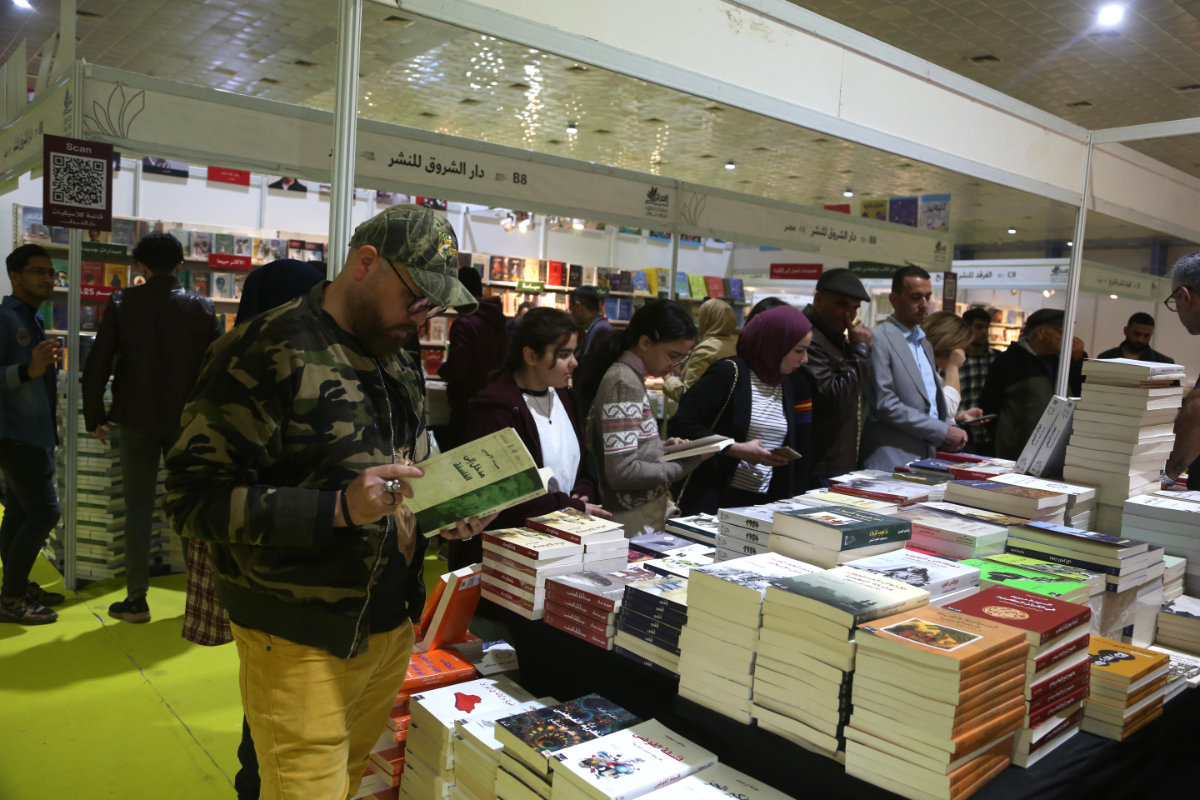

A year later, avid book readers flocked there for the third annual Iraq International Book Fair. It was the largest and most global edition of the event to date, featuring about 800,000 books from 350 Iraqi and international publishers representing 20 countries.

Last year, avid readers flocked to the third annual Iraq International Book Fair. (Ziyad Matti)

The fair was organized by Al-Mada Group, and sponsored by the Association of Iraqi Private Banks and the Iraqi Central Bank. Al-Mada is a media and cultural foundation that was founded in Damascus, Syria, with branches in Beirut and Cairo. In 2003 it moved its headquarters to Baghdad and began publishing Al-Mada newspaper.

The fair was dedicated to the Iraqi philosopher, historian, intellectual and linguist Hadi Al-Alawi (1932-1998), renowned for his studies of Islamic and Arab culture, science, and Chinese and Islamic civilizations. It featured poetry readings, book signings, art exhibitions, and seminars on Iraqi culture and society, and Al-Alawi’s creative journey.

The Iraqis who frequent Al-Mutanabbi Street say that books can safely remain out on display there at night because “the reader does not steal, and the thief does not read.” Despite Iraq’s numerous woes, literature continues to be a mainstay of the nation’s intellectual and cultural life — and one that Iraqis continue to champion through events such as the book fair.

FASTFACTS

Located near the old quarter of Baghdad, Al-Mutanabbi Street was the first book traders’ market in the Iraqi capital.

It is named after 10th-century poet Abu Al-Tayeb Al-Mutanabbi, who was born under the Abbasid dynasty.

It has been a refuge for writers of all faiths and a historic heart and soul of the Baghdad literary and intellectual community.

Still, the uncertain political situation continues to weigh on not just the book-publishing industry but the small and medium enterprises sector in general.

A view of the Baghdad Culture Center being reconstructed. (Supplied)

Prime Minister Mohammed Al-Sudani, who took office in October last year, has struggled to deliver on his promises concerning the economy, security, human rights and corruption.

At the end of January, the wife of the former head of Iraq’s tax authority and two other people were arrested on corruption-related charges. Poverty, unemployment, a lack of local industry, and climate inaction continue to affect the country.

Compounding these problems, bureaucratic red tape and inefficiency at the central level have contributed to a shortage of even basic necessities such as clean water and electricity in many parts of Iraq.

“Because of the security situation over the years, we haven’t had access to bookstores and publishers from outside of Iraq,” Ali Tariq, executive director of the Iraqi Private Banks League, told Arab News.

Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad, long renowned for its booksellers, coffee shops and intellectual scene, was restored and reopened in December 2021. (Photo by Ziyad Matti)

“Iraqis attend (the book fair) from all over Iraq because it allows them to access international books and books from other Arab countries that are not readily available in Iraq.

“A fair like this offers a big opportunity for Iraqis to interact with international publishers, especially (those) from the Arab region.”

Over the past decade, and particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic began, a number of initiatives have been launched across the country encouraging Iraqis, especially the nation’s youth, to develop a love of reading.

In early November, the ninth edition of the “I Am Iraqi, I Read” festival was held on the grassy lawns of Abu Nawas Park in Baghdad. About 35,000 books were distributed free of charge, a massive increase from the 3,000 handed out during the first edition in 2012. The festival is staged each year in different provinces throughout the country.

Books have always been a crucial part of Iraqi heritage. (Photo by Ziyad Matti)

In 2014, a few months after the liberation of the northern city of Mosul from Daesh, the residents there staged their first reading festival. During the occupation of Iraq’s third-largest city, its famous library at Mosul University was bombed and burned down the extremists, an event dubbed “The Book Massacre of Mosul.”

The library, which was established in 1967, was once one of the biggest libraries in Iraq, containing hundreds of thousands of books and manuscripts.

In September 2017, Mosul residents staged a literary festival called “From the Ashes, the Book Was Born.” Attendees were asked to bring one book and donate it to the university’s library. According to the UN, the event collected more than 6,000 books in one day, helping to restock and rebuild the destroyed library.

Despite awareness campaigns, funding to help Iraqi writers get their work in print remains scarce. (Supplied)

Book fairs also take place in other parts of the country, including the southern city of Basra, through the Al-Mada Foundation. In 2021, more than 250 international and Arab publishers took part in the Basra fair, which included a range of cultural activities.

“A love for literature is part of our roots; Iraqis visit Al-Mutanabbi Street on a regular basis now,” said Tariq. “There is a movement now within the population to increase general awareness and emphasize the importance of reading, particularly for the younger population.”

Despite awareness campaigns, however, funding to help Iraqi writers get their work in print remains scarce.

“There are many Iraqi writers but there is no budget to publish their books,” said Al-Khrayfawee, who is also the vice president of the Story Club for the Writers Union of Najaf.

“Iraqis love literature, history and learning about the culture of other people. It’s part of our ancient heritage, like our classical literature and love for poetry.”

Despite awareness campaigns, funding to help Iraqi writers get their work in print remains scarce. (Supplied)

Notwithstanding the many challenges, book fairs and festivals create more opportunities for Iraqi booksellers, writers and publishers, Al-Mada Group’s Jihad said, as well as hope of investment from the private sector in the region and beyond.

“It’s a win-win situation,” she said. “More and more people attend the fairs each year. We have this culture of reading in Iraq, of buying and selling books.

“The Iraqi writers, publishers and book sellers meet vendors from around the region and the world. These exchanges create new business. Our hard work is paying off because each year, more Iraqis and international visitors are attending.”