Like their fellow-ideologues in the former Soviet Union, communist officials in Beijing have kept their promise: They will answer dissent with repression. In China today, if you’re the member of an ethnic minority with a complaint, that you are rash enough to air in public, expect to be dragged into “court” to face a life sentence.

That’s what happened to prominent Uighur intellectual Ilham Tohti last Tuesday. Tohti is widely respected abroad as a moderate voice within China’s eight million-strong Muslim Uighur community, who inhabit Xinjiang Province in the country’s far northwestern corner. The charges were advocating separatism, criticizing the government and “voicing support for terrorists.”

Tohti insisted during the two-day trial in Urumqi, the capital — during which lawyers were prevented from calling witnesses for the defense — that he has always opposed separatism and that he had spent his life as an economist, commentator and activist trying to promote better relations between Uighur and China’s Han majority — a majority that emerged in Xinjiang as a consequence of Beijing’s efforts in recent decades to turn the Uighur into a minority in their own homeland by encouraging Hans to settle in the province.

Probably what clinched it at the trial was the fact that Tohti had set up a website sharply critical of government policies toward Xinjiang, offering an alternative narrative to that of the government’s. (Seven students who worked for the website have been indicted and face trials.)

The verdict was so harsh that it shocked even critics of China’s dubious legal system, and highlighted the government’s brutal repression of of Uighur dissent. “There’s so thorough and transparent a miscarriage of justice as to take one’s breath away,” Elliot Spencer, an expert on China’s minorities at Indiana University, told the Washington Post. “By no stretch of the imagination — even the authoritarian imagination — could this be considered a fair trial. The severity of the sentence stands in inverse proportion to the substance of the charges.”

That’s not the first time China has cracked down on prominent Uighur intellectuals struggling for human rights in the face of communist domination of their community. In 1999, Rubiya Kadeer, the revered Uighur philanthropist and at one time high official in China’s National People’s Congress, was arrested, summarily tried and jailed for well over six years, two of which in solitary confinement in notoriously brutal conditions.

International pressure eventually brought about her release and exile to the United States, where she joined her husband, Sidik Rouzi, also an Uighur political dissident who had served eight years in a Chinese prison before the US granted him asylum. Two of their sons remained incarcerated back in China and a daughter under house arrest — presumably held as punishment for their parents’ activism.

When today you research the history of Xinjiang — as we all had to research the history of Chechnya in the mid-1990s — you stumble upon a land suffused with the stuff of legend. Along the ancient Silk Road where Europe, Asia and Russia converge, stands the ancient homeland of the Uighur, a nation with its own rich culture, Turkic language and yen for independence — or at least independence from communist intrusiveness into its way of life.

What propels the Chinese government, you ask, to launch this relentless campaign in Xinjiang against a people who had historically not evinced violence in their interaction with the outside world? Analysts appear to be convinced that the campaign is in part fueled by Beijing’s determination to wrest full control over the Uighur nation’s vast oil reserves.

That may very well be true. But let’s not overlook another important reason: The nature of the totalitarian impulse imbued in any communist system of government, an ideological system too scurrilous to produce those charities of the imagination which are essential to a sense of the humane in our humanity. Who has, for example, forgotten those savageries that the Soviet Union — and later in its incarnation as the Russian Federation — had in its time inflicted on minorities under its control, particularly in the 1990s in Chechnya?

One thing is plain: Beijing’s policies in Xinjiang will only exacerbate conflict there, and as the World Uighur Congress said in a statement following the dreadful Ilham Tohti verdict last Tuesday, it will “push more Uighur toward violence.”

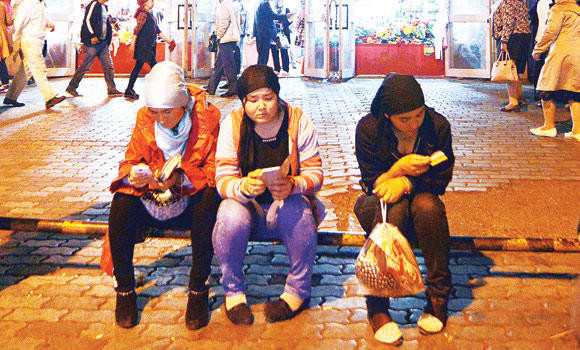

Plight of Uighurs in China

Plight of Uighurs in China