DUBAI: The brewing global food crisis will have a “huge impact” on the Middle East and North Africa, whose populations and economies have suffered “a critical blow” owing to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

That is according to Dr. David Meszaros, a technology entrepreneur and CEO of SmartKas, an agritech company that is building the largest smart farm in the Netherlands using artificial intelligence, drones and robotics.

“If we’re talking about today, if we’re talking about the next few weeks, there’s a huge impact for them,” he told Katie Jensen, the host of “Frankly Speaking,” the video interview show featuring leading regional and international policymakers and business leaders.

Meszaros also revealed plans to build a “mega smart farm” — run completely sustainably, completely autonomously, using only renewable sources of energy and water — to provide food for the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

Speaking more broadly, he said the world can feed 10 billion people by 2050 but not with the current food system. “We’re going to run out of food within the next decade or so,” he said.

The comments come as the UN warns that global hunger levels are at a new record, with food prices about 30 percent higher since the outbreak of the war, food exports dropping significantly worldwide, and inflation soaring in many countries.

In the interview, Meszaros also offered his take on the real reasons for the food crisis, who will suffer most, why new technologies could be the solution and whether can they materialize quickly enough.

Referring to the MENA countries currently facing food insecurity, he said: “Their strong reliance on imported wheat, imported rice, all kinds of grains (and fertilizers) … is completely disrupting their economy, especially the agro-economy. And there is no other choice for the government than to buy food at an increased price to try to meet the demand for food.”

On the upside, according to Meszaros, it is not too late yet as the critical moment will come in another five to 10 years. “If they make the conscious decision to switch now, as in really now,” he said, “then within the next 6-12 months we could see the appearance of smart farms powered by whatever natural resources they have and producing their own food.”

Charles Michel, the EU president, has accused Russia of using food supplies as a “stealth missile” against developing countries, but Meszaros believes the causes of the crisis go deeper than just the war in Ukraine.

“I would say it’s a bit of a stretch to say that (the Russians) are solely to blame. We can all recall that we just had a supply-chain crisis the years prior, as well as an ongoing pandemic — and there are rumors of another wave reaching Europe and the MENA region soon,” he said.

A sunken Ukrainian warship is seen near the pier with the grain storage in Mariupol, scene of heavy destruction in the past weeks amid Russian missile and artillery strikes. (AP Photo)

“We can actually turn back the clock all the way to the 1960s (as) the whole issue started back then. The world’s population is now two and a half times what it was in the 1960s.”

The global food crisis is “an ongoing, long-expected problem that has been brewing and brewing and brewing” which was “never taken seriously,” Meszaros said. As a case in point, he cited the use of fertilizers, which he said has increased by eight times since the 1960s “but because of diminishing returns, its effectiveness has dropped by about 95 percent.”

He likened the situation to running a business without having insurance. “You just hope for the best that nothing goes awry, but then it did,” he said, “and the frequency of these catastrophic events is just increasing.”

Having said that, Meszaros did not play down the importance of Russia’s role as the world’s largest exporter of fertilizers, or that of Russia and Ukraine jointly as the supplier of 30 percent of the world’s wheat supplies and 70 percent of its sunflower oil. Global food supplies are “under extreme stress (which) has been a huge blow not only to the regional, but global food supply as well,” he said.

Fertilizers are stored at a factory compound in Moscow. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of fertilizers. (Shutterstock)

“The problem is that we have increasingly relied on an outdated, very, very old, obsolete food system. This food system positions itself on field farming, and, because of that, there is a non-renewable aspect to it,” Meszaros said.

“There is a continuous new need for fertilizers — whether that’s phosphorus, or nitrogen, or potassium-based fertilizers. There is still a need for (such fertilizers) and you cannot just expect the food system to switch in a matter of weeks or months.

“This is why people are seeing (the Russia-Ukraine) war as a massive trigger that finally made us realize that the current, unsustainable and non-renewable system just cannot continue.”

Meszaros is known for being a big advocate of the autonomous smart farm, having created the biggest of its kind in the Netherlands. But how exactly does it work?

He put it this way: “Imagine you have a farm field. You try to grow strawberries on it. Usually, you have a yield of 10 to 15 metric tons on one hectare. But on the same amount of land, when a 10 or 12-layer vertical farm is built by SmartKas, you can grow above 2,000 metric tons — that is, approximately 200 times more high-quality, pesticide-free and sustainably grown fresh strawberries.

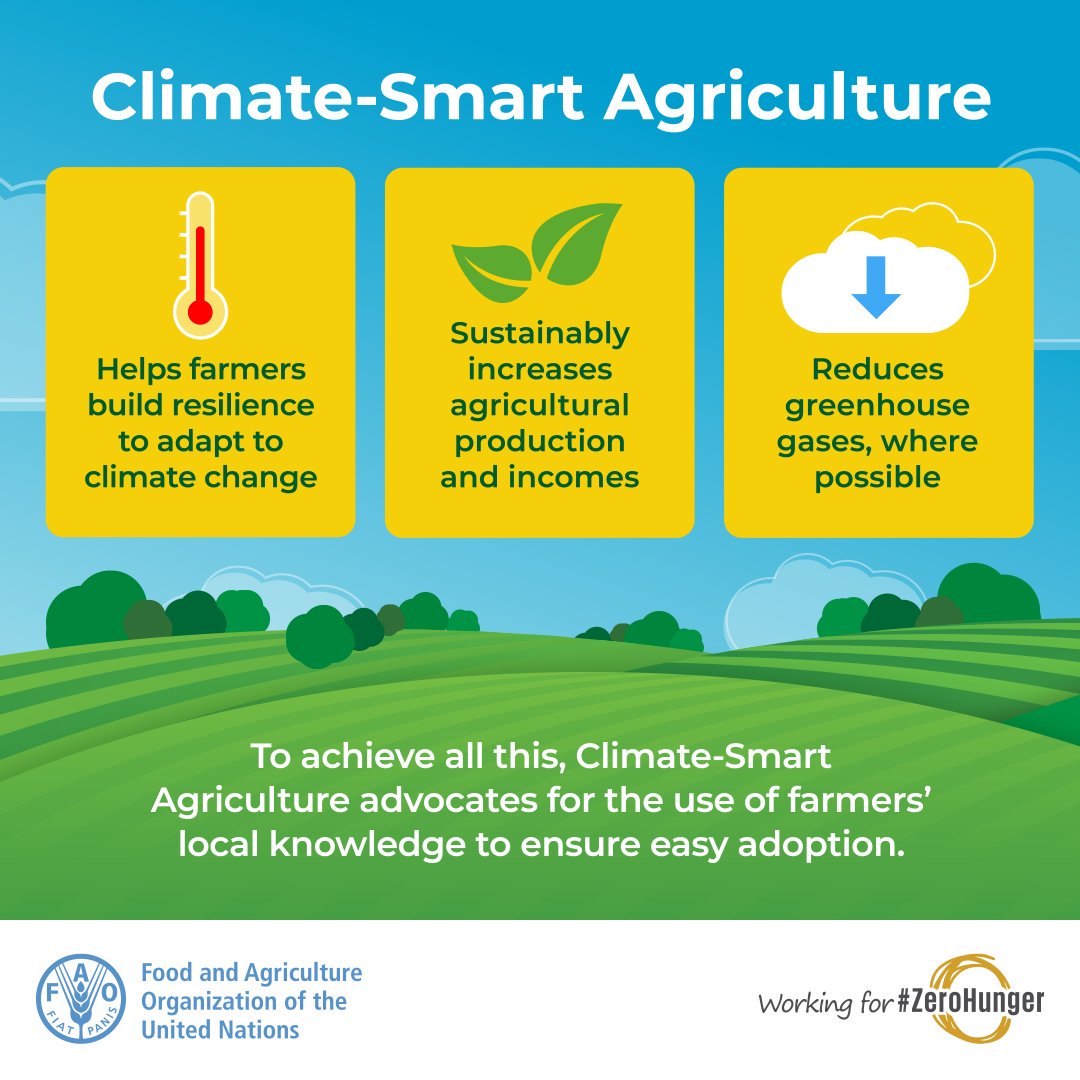

The Food and Agriculture Organization is advocating the adoption of smart farming to meet the world's food needs amid worsening climate change. (Courtesy: FAO.org)

“Not only that, but those are grown 24/7 — so from Jan. 1 until Dec. 31 — and they are grown right next to the city where they are sold.

“We are recirculating the water, we are using solar or wind or whatever energy is possible for us — and this is grown all pesticide-free and sold locally. So, we are cutting out the middleman, there’s no import, there’s no export and, by orders of magnitude, higher amounts. I am here in the Amsterdam location, but we also have a location in London, we have a R&D facility in Hungary and we are building a massive greenhouse in Brazil.”

Elaborating on his plans for creating a “mega farm” for several Gulf Cooperation Council countries, he said discussions are underway with government officials as well as individuals in the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

“What we believe in, is that, especially for the GCC countries, we could build one massive mega facility that — running completely sustainably, autonomously and using only renewable sources of energy and water — could feed the three countries,” he said.

Discussions are under way to create a “mega farm” for several Gulf Cooperation Council countries, says SmartKas CEO David Meszaros. (AN photo)

Meszaros envisions “a triangle format, where one equal piece of the triangle would be in one of the three countries,” supplemented by the introduction of “autonomous electric vehicles — trucks, essentially — for supplying fresh fruits and vegetables to the largest cities of these three countries.”

With regard to the location of the project, he said: “We can pick the most ideal position from a climate perspective, from a power-line perspective, from a water perspective etc.”

As for the total cost, he believes it would be between $900 million and $1.1 billion, with a capacity for producing “about 50,000 tons of fresh fruits and vegetables, which, according to our studies, would be more than enough for the fresh fruit and vegetable supply for these countries.”

Meszaros hopes to rely heavily on solar because, as he put it, “the sun is not in short supply in these countries, land is available and you can utilize it, and there are newer and newer technologies in photovoltaic, or PV, panels — some elevated, some transparent.”

He said SmartKas is experimenting with transparent PVs “which allow for even more energy generation per target area,” adding that “we have automated robots, strings, drones that can clean (dust and sand) from the panels regularly without human intervention.”

With regard to water supplies, he said there are some potential solutions. “Number one, because the systems themselves are hermetically closed, anything we can recycle. The recycling will not be perfect, we will have some losses. So, we would introduce two water-capture units,” he said.

“One would be a desalination plant and the other one would be an atmospheric water-generation unit that captures the humidity from the air. And, alongside the coastline, we have already done on-site studies on this. There’s just enough humidity in the air to capture between four to six thousand liters of water per unit per day.”

Meszaros said SmartKas “already has investors signed on … in all three countries,” and is talking to European investors and European public entities as well.

“We expect to finish the early-stage development pre-engineering and designs in the next two years, and then afterwards we can talk about construction,” he said. “Definitely not in the next two years. Probably three, four years (from now) is when we will see signs of this project.”

On a final note, Meszaros outlined some steps that he thinks should be put in place if the world is to feed a projected population of 10 billion by 2050.

“The first is to cut the reliance on fertilizers and inefficient farming methods,” he said.

“Not every country needs to have an autonomous AI-run farm. You can start small. You can use drones to better divide the pesticides, then you can use certain foil technologies, polytunnel technologies — what Spain uses, what Morocco uses — to protect the crops and then slowly every single country can transition.

“But, in essence, using technology and innovative solutions is the key towards providing food security in the world.”