KABUL: When the Taliban captured Kabul on Aug. 15, 2021, amid the withdrawal of US-led forces from Afghanistan, the group’s stunning return to power marked the end of two decades of warfare, which had killed tens of thousands of Afghans on their own soil.

One year on, with the country pauperized and isolated on the world stage under its new leadership, life for ordinary Afghans has changed — largely for the worse.

During their first stint in power, from 1996 until late-2001, the Taliban declared an Islamic emirate, imposing a strict interpretation of Islamic law, enforced with brutal public punishments and executions.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Women and girls were removed from public life, prevented from working or receiving an education, and even barred from leaving the house without the all-enveloping niqab and a male relative to chaperone them.

In Oct. 2001, US-led forces invaded Afghanistan and removed the Taliban from power, accusing the group of sheltering Osama bin Laden, the Al-Qaeda leader deemed responsible for the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on the US that killed almost 3,000 people.

Edi Maa holding her baby receiving treatment for malnutrition at a Doctors Without Borders (MSF) nutrition centre in Herat. (AFP)

What followed were 20 blood-soaked years of fighting between the NATO-backed Afghan national forces and Taliban guerrilla fighters intent on retaking power.

While under the Western-backed administration, Afghanistan made progress with the emergence of independent media and a growing number of girls going to school and university.

However, in many regions beyond the big cities, Afghans knew only war, depriving them of the many development projects implemented elsewhere by foreign donors.

Now that US-led forces have withdrawn and the Taliban has traded guerrilla warfare for the day-to-day running of the country, security has greatly improved.

During their first stint in power, from 1996 until late-2001, the Taliban declared an Islamic emirate, imposing a strict interpretation of Islamic law, enforced with brutal public punishments and executions. (AFP)

“We only saw war in the past several years. Every day, we lived in fear. Now it’s calm and we feel safe,” Mohammad Khalil, a 69-year-old farmer in northwest Balkh province, told Arab News. “We can finally breathe.”

But the uneasy peace has come at a cost.

Afghanistan’s aid-dependent economy has been in free fall since the Taliban returned to power. Billions of dollars in foreign assistance have been suspended and some $9.5 billion in Afghan central bank assets parked overseas have been frozen.

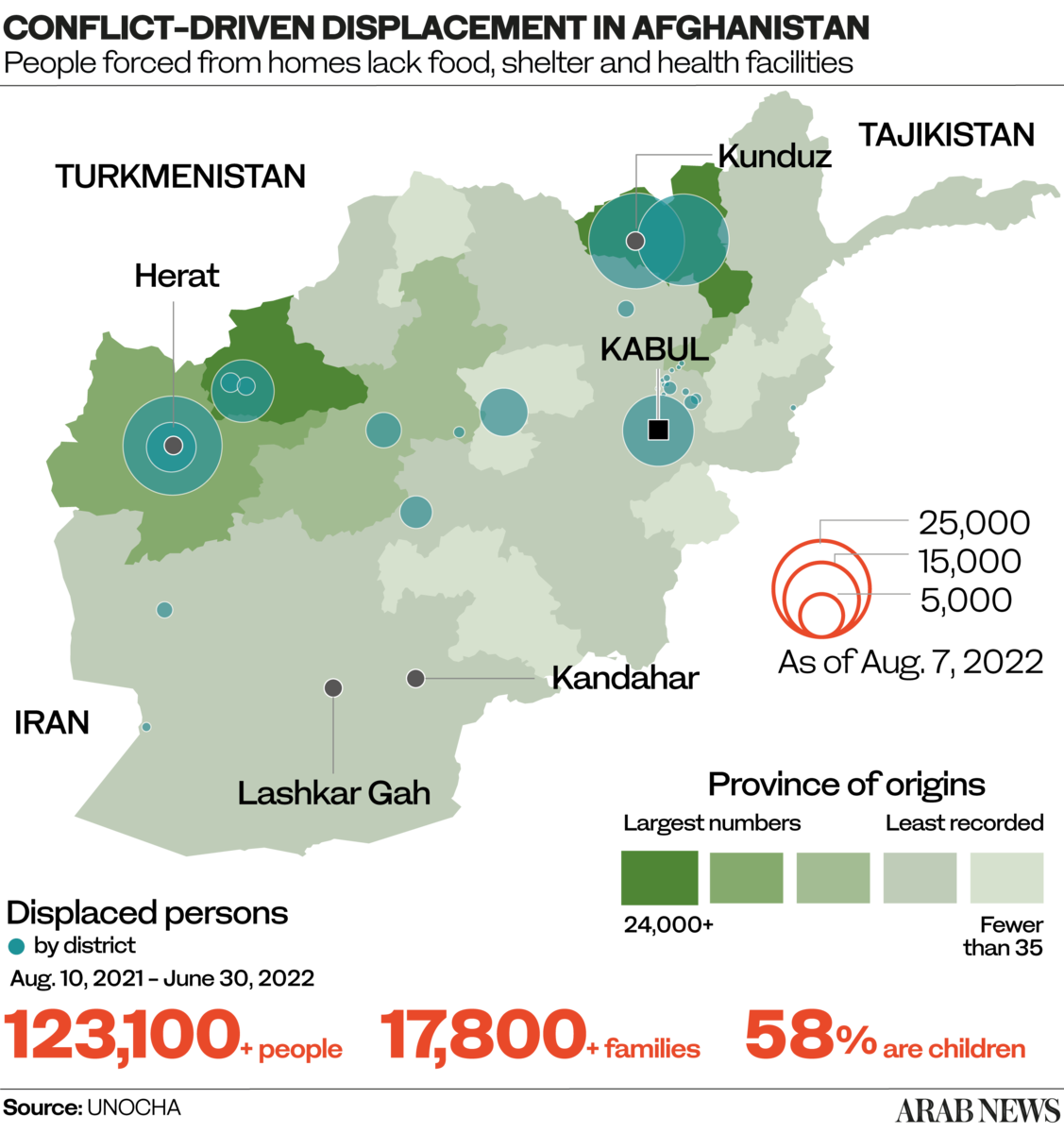

Denied international recognition, with aid suspended and the financial system in paralysis, the UN says that Afghanistan faces humanitarian catastrophe. About 20 percent of the country’s 38 million population are already on the brink of famine.

Afghanistan: One year since the Taliban takeover

Aug. 15, 2021 - Taliban campaign culminates with the fall of Kabul.

Aug. 30 - The last US troops depart Kabul airport after evacuating more than 120,000 people over 17 days.

September - A new interim government is unveiled. The Taliban bring back the feared religious police.

October - More than 120 people are killed in two Daesh-claimed mosque blasts in Kandahar and Kunduz.

Jan. 2022 - Deprived of aid, Afghanistan is plunged into a deep economic and humanitarian crisis.

March - The Taliban block secondary school girls from returning to class. Government employees must grow beards.

May - Women and girls are ordered to wear the hijab and cover their faces when in public. Women are banned from making long-distance journeys alone.

June - More than 1,000 people killed and thousands left homeless in a massive earthquake.

August - The US announces the killing of Al-Qaeda leader Ayman Al-Zawahiri in a drone strike on his Kabul hideout.

The price of essential commodities has soared as the value of the Afghan currency has plummeted. A continuing drought has further aggravated the situation in rural areas.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies estimates about 70 percent of Afghan families are unable to meet their basic food needs.

“Most of the time we eat bread and drink tea or just water. We can’t get meat, fruit or even vegetables for the children. Only a few people have goats or cows to feed the children with milk,” Khalil said.

In the capital, Kabul, food is widely available, but few can afford a vaied and nutritious diet.

“There are plenty of food items in the market, but we don’t have the money to buy them,” Mohammad Barat, a 52-year-old daily wage earner, told Arab News.

The looming catastrophe is not only one of shocking levels of poverty, but also lost hope and opportunities.

Tens of thousands of Afghans fled the country over several chaotic days last August, when US forces and their coalition partners hastily airlifted Afghans from Kabul airport. Many others, including professionals, have since followed in their footsteps.

“Doctors are leaving, engineers are leaving, professors and experts are also leaving the country,” Abdul Hamid, a student at Kabul University, told Arab News. “There’s no hope for a better future.”

Those who worked for the deposed Western-backed administration have been removed from public life, particularly women, who are now forced to wear face coverings, banned from making long-distance journeys alone, and prevented from working in most sectors beyond health and education.

Women face a growing number of restrictions in their daily lives; right, Taliban fighters in Kandahar celebrate the US withdrawal. (AFP)

Education, too, has been strictly limited for women, even though allowing girls into schools and colleges has been one of the international community’s core demands since the Taliban retook control of the country.

In mid-March, after months of uncertainty, the Taliban said that they would allow girls to return to school. However, when they arrived at schools around the country to resume studies, those above the age of 13 were ordered to return home.

In a last-minute decision, the Taliban had announced that high schools would remain closed for girls until a plan was ready to receive them in accordance with Islamic law.

Almost half a year later, teenage girls fear they will not return to the classroom anytime soon.

“There’s no reason for banning girls from school,” Amal, an 11th grade student at Rabia Balkhi High School in Kabul, told Arab News. “They just don’t want us to get an education.”

Now that US-led forces have withdrawn and the Taliban has traded guerrilla warfare for the day-to-day running of the country, security has greatly improved. (AFP)

Despite repeated hints by the predominantly Pashtun, Islamic fundamentalist group that experience and the passage of time have softened its rough edges, the streets of Kabul increasingly resemble the Taliban-governed pre-2002 era.

Since the restoration of the Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, which enforces the group’s austere interpretation of Islam, traditional clothing, turbans and burqas have replaced suits and jeans, which only a year ago had been considered normal attire in the Afghan capital.

Key symbols of the nation’s identity are also changing, with the white and black banner of the Taliban now appearing on government buildings and in public spaces, gradually replacing Afghanistan’s tricolor, despite earlier pledges it would not be changed.

For some, the replacement of the old national flag is more than symbolic, and is indicative of the Taliban’s hijacking of the country.

“It doesn’t represent any government or regime. The Taliban could keep both,” Shah Rahim, a 43-year-old resident of Kabul, told Arab News.

“The flag is a representation of our nation, our values and our history.”