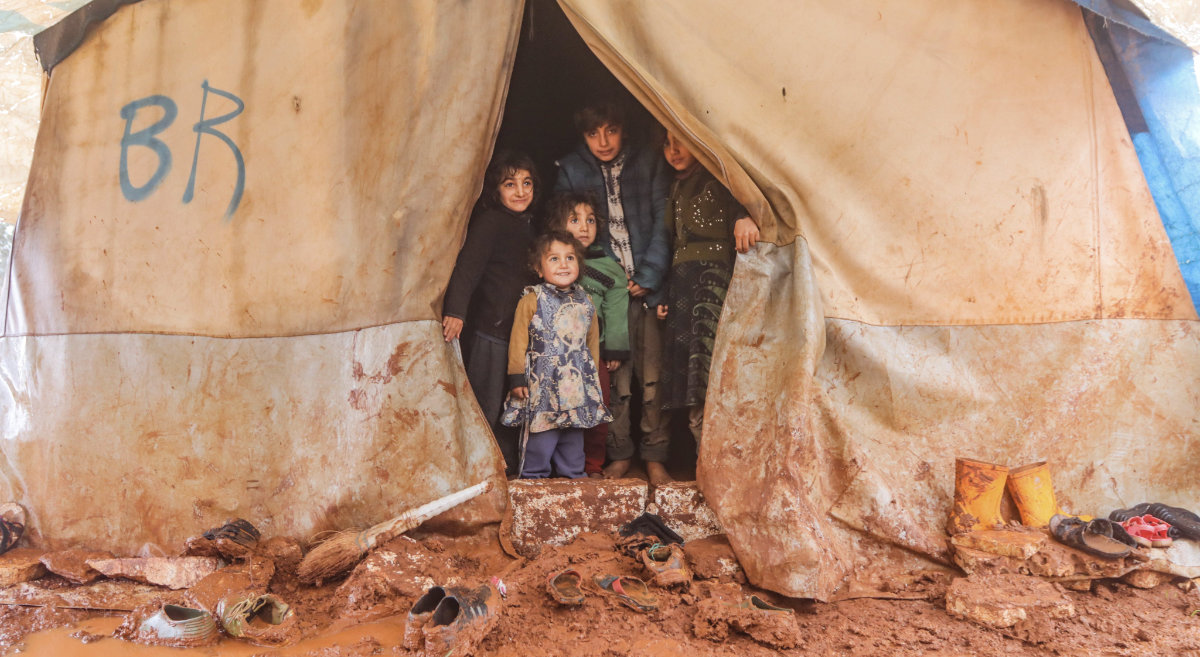

LONDON: Rescued from under rubble six months ago, Hiba, who has not yet turned six, lost her entire family and part of her foot in Syria’s deadly earthquakes in February. In need of constant care, she now lives with distant relatives in an overcrowded displacement camp.

Hiba, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, is one of thousands of children orphaned by two temblors that struck southern Turkiye and northern Syria on Feb. 6, which upended the lives of at least 2.5 million children in Syria alone, according to UNICEF.

The 7.8-magnitude earthquake near the Turkiye-Syria border in the early hours of the morning was followed by another one almost as strong, resulting in one of the biggest humanitarian disasters to strike the region in recent times.

Tens of thousands of people were killed and many more injured. Innumerable buildings, including homes, schools and hospitals, collapsed, leaving large swathes of the local population exposed to harsh winter conditions.

Rebel-held Jindires, in Aleppo province in northwest Syria, was relatively more fortunate in the sense that it received humanitarian aid fairly soon after the February 6 earthquakes. (AFP file photo)

Children who lost all adult family members in the earthquakes either moved in with distant relatives, many of whom had themselves been displaced by the devastation, or had to fend for themselves.

The repercussions of the natural and humanitarian disasters in northwest Syria have been especially harmful to orphaned children with no adult relatives in the area. They are vulnerable to various forms of abuse, trafficking and mental-health disorders.

The scale of the suffering being endured by separated or orphaned children in northwest Syria “is vast, multifaceted and deeply concerning,” said Hamzah Barhameyeh, advocacy and communication manager at World Vision, an international child-focused charity.

“The situation was already dire owing to the conflict, but the earthquakes have significantly compounded the hardship faced by these children, affecting various aspects of their well-being and development.”

A volunteer from the humanitarian organization Space of Peace attends to children at a refugee center for people displaced by the February earthquakes in northern Syria. (Supplied)

The challenges, according to Barhameyeh, include “trauma and psychosomatic problems” as well as “physical injuries and disabilities, inadequate health support and disrupted education.”

Additionally, there are concerns over heightened risks of child marriage and child labor, not to mention recruitment by armed groups in a war-torn region.

“(Boys) are at higher risk of becoming separated, unaccompanied, or ending up living on the streets,” Barhameyeh told Arab News. “Adolescent boys face the substantial danger of being recruited into armed groups.

A photo taken on May 23, 2023 shows Syrian kids getting ready to board a bus turned into a traveling classroom for children left homeless and school-less in Jindires, Aleppo. Aid groups are worried that many orphaned children are vulnerable to recruitment by rebels. (AFP file photo)

“There is also a noticeable trend of child labor and violent behavior, increase in substance abuse and run-ins with the law. These experiences are predominantly common in the case of boys.”

Diana Al-Ali, founder of a local nongovernmental organization (NGO) called Suriana, says that during her encounters with children in displacement camps, many rush forward to hold her hand, seeking comfort and safety.

Apparently, even children who have not been orphaned often endure beatings by parents who themselves are under a lot of stress.

The Turkiye-Syria earthquake has orphaned many Syrian children against a backdrop of mass displacement, destroyed schools and limited access to water and sanitation. (Supplied)

“Many children are in urgent need of emotional support,” Al-Ali told Arab News, citing cases of young people attempting suicide owing to untreated trauma-related mental illness.

Among the children she regularly supports is a girl who refuses to step on the ground and is terrified of ants, convinced that, just as in children’s cartoons, the crawling creatures shake the ground when they move.

Similarly, Hiba, who needs regular medication and trips to the hospital, is terrified of walls and ceilings; the shock she suffered during the earthquake was so severe that she still shows no reaction when spoken to.

A volunteer from the humanitarian organization Space of Peace attends to children at a refugee center for people displaced by the February earthquakes in northern Syria. (Supplied)

Al-Ali says her charity has been providing children and their guardians with cash, foodstuffs, medicines, diapers and even entertainment activities, but she describes the unmet humanitarian needs in the quake-hit region as enormous.

The UN Security Council failed in July to renew authorization for UN humanitarian aid deliveries to Syria’s rebel-held northwest through the Bab Al-Hawa border crossing, cutting off a vital lifeline for more than four million aid-dependent people.

On July 11, a day after Resolution 2672 expired, two rival resolutions to allow the continuation of UN aid flow from Turkiye were vetoed by Russia on the one hand, and the US, the UK and France on the other.

Compounding the suffering in Syria’s northwest is a searing summer heatwave, which has seen temperatures exceed 40 degrees Celsius and fires break out in displacement camps in Idlib and northern Aleppo, according to a report by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

INNUMBERS

58,000 Deaths in southern Turkiye and northwest Syria in Feb. 6 earthquakes.

200,000 Buildings damaged or destroyed, including schools and hospitals.

2.5 million Children impacted by earthquakes in Syria alone (UNICEF).

Mental health support remains inaccessible for most, said Al-Ali, recounting the plight of a child battling epilepsy while living in a tent. “He needs costly medication every month, and his father was killed in the conflict,” she said.

Al-Ali added that many of the tents in question are so cramped that there is no space to lie down, forcing individuals to remain seated in one spot for long periods of time.

“Organizations operating in the region did not provide mental health support when the quake struck,” she said, adding that the humanitarian focus on the two cities of A’zaz and Jindires meant that other areas failed to receive adequate attention.

Children's needs in NW Syria are soaring & more, not less, humanitarian access is needed. (World Vision)

“There were not many organizations (operating) here when the quakes struck, so we relied on personal efforts alongside the NGOs Violet and Shafak, which provided bread.

“There is not enough funding dedicated to children’s well-being. We are the only ones providing recreational activities for children, and mental health support sessions.

“We have programs dedicated to helping minors feel safe and each child is assessed to identify their needs.”

Among the many factors militating against the protection of orphaned and separated children, according to World Vision’s Barhameyeh, is the loss of civil documentation during the conflict and the earthquakes.

Describing the situation as “highly complex and challenging,” he said that the absence of the documents poses “a significant barrier” to the achievement of a normal life by these children.

Elaborating on the problem, Barhameyeh said that while there are nongovernmental organizations providing protection against trafficking and other threats, “these services are not fully integrated or collaborative with local councils,” with the “absence of formal child-protection mechanisms” also playing a role.

With limited funding allocated for child protection, millions of children remain not only vulnerable, but also in a state of politico-bureaucratic limbo. (AFP)

A lack of proof of legal identity “severely hinders” children’s “ability to exercise their rights,” he said, adding that the documentation problem is becoming alarmingly “multi-generational” as more children are born in displacement to parents “who themselves lack proper documents.

“An additional layer of complexity is being introduced by various authorities issuing their own documents, leading to a proliferation of documentation.”

According to Barhameyeh, there may be short-term benefits for the holders of the documents in areas under the control of the issuing authorities, but they could cause serious security problems in the long run, “including arbitrary arrest and detention by the government of Syria, particularly outside northwest Syria.”

With limited funding allocated for child protection and the risks greatly outweighing the resources available, millions of children remain not only vulnerable, but also in a state of administrative limbo.

The broad consensus of NGOs and charities active in the region is that unless efforts to protect children are intensified, what awaits them is a grim and uncertain fate.