LONDON: Violent extremist groups are exploiting public outcry surrounding the war in Gaza to fan the flames of radicalization, recruit followers, and encourage lone-wolf attacks in the West, counterterrorism officials have warned.

Since the Hamas-led attack of Oct. 7, which sparked Israel’s retaliation in Gaza, security chiefs have warned of a dramatic rise in violent Islamist tendencies, online terrorist propaganda, and the number of individuals flagged to authorities.

Speaking at the Munich Security Conference on Saturday, Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan said the provocative actions of Israeli forces deployed in the Gaza Strip would inflame feelings in Arab and Islamic countries, especially with the death toll approaching 30,000.

Since the Hamas-led attack of Oct. 7 and the devastating Israeli military retaliation, US and European security chiefs have warned of a dramatic rise in violent Islamist tendencies. (AFP)

He warned that these incidents could serve the ideologies of terrorism and extremism around the world.

Last month, Matt Jukes, head of UK counterterrorism policing, said events in the Middle East had created a “dangerous climate” in which anger at Israel’s actions and alleged Western inaction is feeding grievances that can be exploited by extremist groups.

“That puts us at a point in communities, on the street and online, which would lead us to describe what has happened in the Middle East as a radicalization moment,” Jukes said in a statement on Jan. 19.

“These are the moments when a mixture of outrage, grievance and a set of enduring factors have the potential to influence those susceptible to being pushed towards terrorism.”

Similar concerns were raised in the immediate aftermath of the Hamas-led attack by the head of MI5, Ken McCallum, who told the BBC that “lots of would-be-terrorists in the UK draw inspiration through their distorted understanding of what is happening in other countries.”

Likewise, in the US, FBI Director Chris Wray said: “We cannot and do not discount the possibility that Hamas or other foreign terrorist organizations could exploit the conflict to call on their supporters to conduct attacks on our own soil.”

Elizabeth Pearson, a counterterrorism expert and author of the recently published book “Extreme Britain,” believes the Israel-Hamas conflict is acting as “a lightning rod” for radicalization — a phenomenon made worse by preexisting grievances.

“This particular conflict has always been a symbolic vessel for different identities to feel — and also become — marginalized,” Pearson, who heads the master’s program in terrorism and counterterrorism studies at Royal Holloway, University of London, told Arab News.

“I’ve talked to Islamist activists in the UK and they explicitly set out to use this conflict and the plight of Palestinians to gain new members. The narrative of Muslim victimization and powerlessness is key here. Islamist responses are always: ‘The only way to solve this problem is to join our group.’”

Experts suggest there are several ways in which extremist groups may try to spin events in the Middle East to fit a particular worldview. For Alan Mendoza, executive director of the Henry Jackson Society, these follow a familiar format.

Saudi Arabia Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan said the provocative actions of Israeli forces deployed in the Gaza Strip would inflame feelings in Arab and Islamic countries. (AFP)

“The customary way the narrative emerges is along the lines of: ‘The West is corrupt and hypocritical,’” Mendoza told Arab News.

“‘Its allies kill innocent Muslims while it supplies them weapons and provides diplomatic coverage for them to do so. These same Western countries are increasingly oppressing their Muslim populations at home too. Come and join us to liberate our people.’”

The implications of this climate of radicalization in the UK are being expressed in several ways. The most obvious since the onset of the Gaza crisis has been the sudden spike in hate crimes and hate speech on social media.

“We are seeing a massive escalation in Islamophobia and, in particular, antisemitism,” Emily Winterbotham, director of the terrorism and conflict program at London’s Royal United Services Institute, told Arab News.

“This is recognized by UK intelligence services. Protests and acts of antisemitism, Islamophobia, vandalism, and social tensions increase the environment of radicalization.”

Statistics from the London Metropolitan Police show there were 218 antisemitic incidents between Oct. 1 and 18 last year — up from 15 during the same period in 2022. Likewise, there were 101 Islamophobic offenses, up from 42.

“We’ve also seen a 12-fold increase in hateful social media content referred to specialist police officers of the Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit,” said Winterbotham. “This is primarily antisemitic content and from users not previously on police radar.”

And it is not just Islamist groups that have reportedly seized upon events in the Middle East to push an extremist narrative, recruit followers, and incite violence.

“Far-right groups in the UK are using the conflict to further delegitimize Islam and Muslims, siding with Israel in order to further an anti-Muslim agenda,” said Pearson.

According to Metropolitan Police figures, the amount of terrorist material appearing online surged to 15 times the level it was prior to Oct. 7. (AFP)

“Polarization, Islamophobia and antisemitism in wider society justify hatred and violence … It is the polarization, the inability to empathize with others, and ultimately their dehumanization, which is a key characteristic of radicalization.”

Anas Al-Tikriti, CEO and founder of the Cordoba Foundation, rejects the notion that Islamists or Muslims in general are solely responsible for the apparent rise in extremist content since the conflict began.

“I would suggest that any conflict, particularly the magnitude and obviously the territory that we’re talking about over the course of the past four months, will have created an increase, probably a significant increase, in radicalized tendencies on both sides,” he told Arab News.

“But why just focus on the Muslim side? Why not, for instance, talk about what’s happening on Zionist platforms and accounts?”

He added: “I doubt that there is anyone who is either shocked or surprised by the fact that the conflict in the manner and shape and form and the images that we have been engulfed with over the course of the conflict will have led to such tendencies. But I reject, I absolutely and utterly reject … that these are exclusive to Muslim circles.”

According to Metropolitan Police figures, the amount of terrorist material appearing online surged to 15 times the level it was prior to Oct. 7, before settling at a level seven times greater.

“That is extraordinary and demonstrates the volume and intensity of online rhetoric around the ongoing conflict,” said counterterrorism chief Jukes in his January statement.

Anas Al-Tikriti, CEO and founder of the Cordoba Foundation, says when international community agencies such as the UN fail to protect people’s lives, people will feel that they need to take things into their own hands. (AFP)

“We always see spikes after terrorist incidents, but what we have seen since Oct. 7 is higher and more sustained than ever before. This is a conflict and these are tensions playing out online in a way which, in our experience, is unprecedented.”

What is less clear is whether this climate of radicalization is confined to the online sphere or is now evident in communities.

“Although the greatest forum for radicalization in this conflict has occurred online, video has emerged from several mosques of Friday sermons that can only be designed to inflame the views of those listening,” said Mendoza.

“Campuses have also not been immune to the greater trend of protest marches where extremist rhetoric is often heard and slogans displayed.

“The implications are clear that if the spread of this activity is not checked, then it will not only continue but also worsen as the boundaries for what is acceptable are pressed.”

Counterterrorism experts view online activity as a good — if imperfect — barometer of radicalization in public life. The dilemma for counterterrorism authorities is recognizing the difference between chatter and an impending real-world threat.

“Much of this extremist content and radicalization is taking place in the online space, which mirrors but exaggerates what is happening in real life,” said Winterbotham.

“There is still insufficient understanding of the relationship between online extremist content and offline behavior. It is important to work to identify risk factors, language patterns and behavioral indicators, especially in the online space to help identify which extremist individuals and groups pose a risk of violence.”

The implications of this climate of radicalization in the UK are being expressed in several ways. (AFP)

There have lately been troubling examples of how terrorist material posted online can influence public opinion in unexpected ways.

In November, “Letter to the American People,” a 2002 manifesto penned by Osama bin Laden, suddenly went viral on TikTok, with influencers reading parts of the document and characterizing the former Al-Qaeda leader as a hero.

“The fact that Gen Z sees content in these videos as more credible than mainstream news is deeply concerning and benefits Al-Qaeda and other violent extremist groups,” said Winterbotham.

“We are also witnessing the growth of conspiracy theories. This is nothing new, but it is the combination of these with extremist narratives that is distinctive. Given the polarization and radicalization of the debate over Israel and Gaza, a minority of Britons are engaging with often highly prejudiced conspiracy theories.”

Given this growing constituency of radicalized individuals, experts suggest it is not beyond the realms of possibility for domestic and foreign terrorist organizations to incite or actively carry out violent acts on British soil.

The UK terror threat level is currently rated as “substantial” — the third of five tiers — which means that an attack is considered likely. If terrorist groups decide to mount an attack in the UK, this threat level could rise to “severe” or “critical.”

Experts suggest there are several ways in which extremist groups may try to spin events in the Middle East to fit a particular worldview. (AFP)

“Hamas itself potentially poses a threat to UK soil, and we have seen foiled Hamas plots in Germany and Denmark already last year,” said Winterbotham, referring to the Dec. 14 arrest of four people on suspicion of planning to target Jewish institutions in Europe.

“Possible responses include striking abroad at Israeli embassies, diplomatic facilities, and representatives,” she added.

But it is not just parties to the conflict who might seek out Western targets. Groups like Daesh are also likely searching for an opening.

“Recently, (Daesh) spokesman Abu Hudhayfa launched a new speech, ‘And kill them wherever you find them,’ which encouraged lone actor attacks,” said Winterbotham.

“We’ve already seen an uptick in lone actor attacks since Oct. 7 in Arras, France, Paris, Brussels, and a foiled attack in Las Vegas. Links to Gaza have been made.”

Al-Qaeda might also try to exploit this climate, with recent online activity suggesting the terrorist network is trying to encourage lone wolf attacks.

“In recent months, Al-Qaeda has ramped up its incitements against US-allied Arab governments,” said Winterbotham.

“On Dec. 26, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula relaunched its English-language magazine Inspire, with a video showing scenes from Gaza, protests, and US support of Israel, calling for attacks in America and against Jewish and Western targets, including US, British and French airlines and high-profile figures and containing instructions for home-made explosives.”

Palestine has never been one of Al-Qaeda’s top priorities, says Winterbotham. “Rather, it used Palestine in rhetoric to broaden appeal. However, the presence of Al-Qaeda’s de facto leader, Saif Al-Adel, in Iran is influential.”

Elizabeth Pearson, a counterterrorism expert and author of the recently published book “Extreme Britain,” believes the Israel-Hamas conflict is acting as “a lightning rod” for radicalization — a phenomenon made worse by preexisting grievances.(AFP)

Indeed, given its support for Hamas and other regional proxy groups, including the Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and various Shiite militias in Syria and Iraq, security officials also believe Iran is keen to exploit the climate of radicalization.

In January, it emerged that videos of antisemitic speeches by Iranian generals, given to UK students, were being investigated by the Charity Commission. The regulator was also reportedly looking into chants of “death to Israel” at an Islamic charity’s UK premises.

The talks by members of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, recorded in 2020 and 2021 and which included denial of the Holocaust and references to an apocalyptic war on Jews, added to growing concerns that the IRGC is attempting to radicalize UK Muslims.

Security services have previously warned that the IRGC is inciting violence and plotting to kidnap or kill people on British soil, leading to calls for it to be designated a foreign terrorist organization. Some believe the war in Gaza provides Iran with fresh opportunities.

“Iran’s game here is simple,” said Mendoza. “By posing as the leading international defender of Gaza — even though in reality its support for Gaza has brought complete destruction for Gaza’s Palestinian inhabitants — it is able to channel the emotional rage expressed by the public into solidarity for Iran’s own fight with the West.

“Iran and its proxies hope to use Gaza for their own PR purposes, as can be seen by public support for the Houthis in sections of the West despite the Houthis’ appalling human rights record and theological beliefs.”

To counter the phenomenon of radicalization, the UK government launched Prevent, a system first established in 2007 in the wake of the 7/7 bombings, to allow public institutions to flag individuals exhibiting extremist tendencies.

The rate of these referrals is seen as another barometer of the scale of radicalization at a given moment.

According to counterterrorism chief Jukes, referrals to Prevent were up 13 percent between Oct. 7 and Dec. 31 last year compared with the same period in 2022. Jukes said the increase “is directly related to the conflict in the Middle East.”

But just how effective is the Prevent strategy in stopping ideas from turning into intent?

“One of the issues with programs like Prevent is that they tend to be better at countering ideas by dismantling structured ideological belief systems,” said Winterbotham.

There have lately been troubling examples of how terrorist material posted online can influence public opinion in unexpected ways. (AFP)

“This may be of limited use when addressing issues related to the Middle East and contemporary forms of extremism based on hybrid and mixed ideologies.”

She called for “a more comprehensive engagement, involving a whole-of-society response that combines integrated, non-securitized preventive actions with targeted prevention activities.

“In countering extremist ideas and terrorist groups that aim to undermine democracy, it is more important than ever to establish robust systems of governance that treat all individuals fairly and consistently.

“It is a key principle of our counterterrorism work but much of this goes far beyond counterterrorism.”

Pearson concurs that counter-radicalization policies need to be implemented sensitively — else they make matters worse.

“It’s important that those in charge do not amplify the emotions surrounding this conflict. Effective leadership should serve to calm, not inflame,” she said.

“Labels such as terrorist and extremist have tended to expand in recent years, covering more people and offenses. The UK should take care not to needlessly expand these terms.”

Of course, one way to remove the threat posed by radicalization emanating from the Gaza war would be a resolution to the decades-old Israeli-Palestinian conflict — the cause of so much instability in the Middle East.

“There’s a very reasonable and quite sensible stand that the UK should have adopted many months ago,” said The Cordoba Foundation’s Al-Tikriti.

“That is to call for a ceasefire, which the UK government not only failed to do but went as far as to sack and to punish those who ever uttered the word, and even going as far as to label those who spoke of a ceasefire of being antisemitic, which is utterly absurd.”

Under the circumstances, is there a danger that extremist narratives may seem vindicated if the international community fails to move the dial on the Middle East peace process or if the conflict escalates further in the region?

Arab officials have warned that provocative actions of Israeli forces deployed in the Gaza Strip would inflame feelings in Arab and Islamic countries. (AFP)

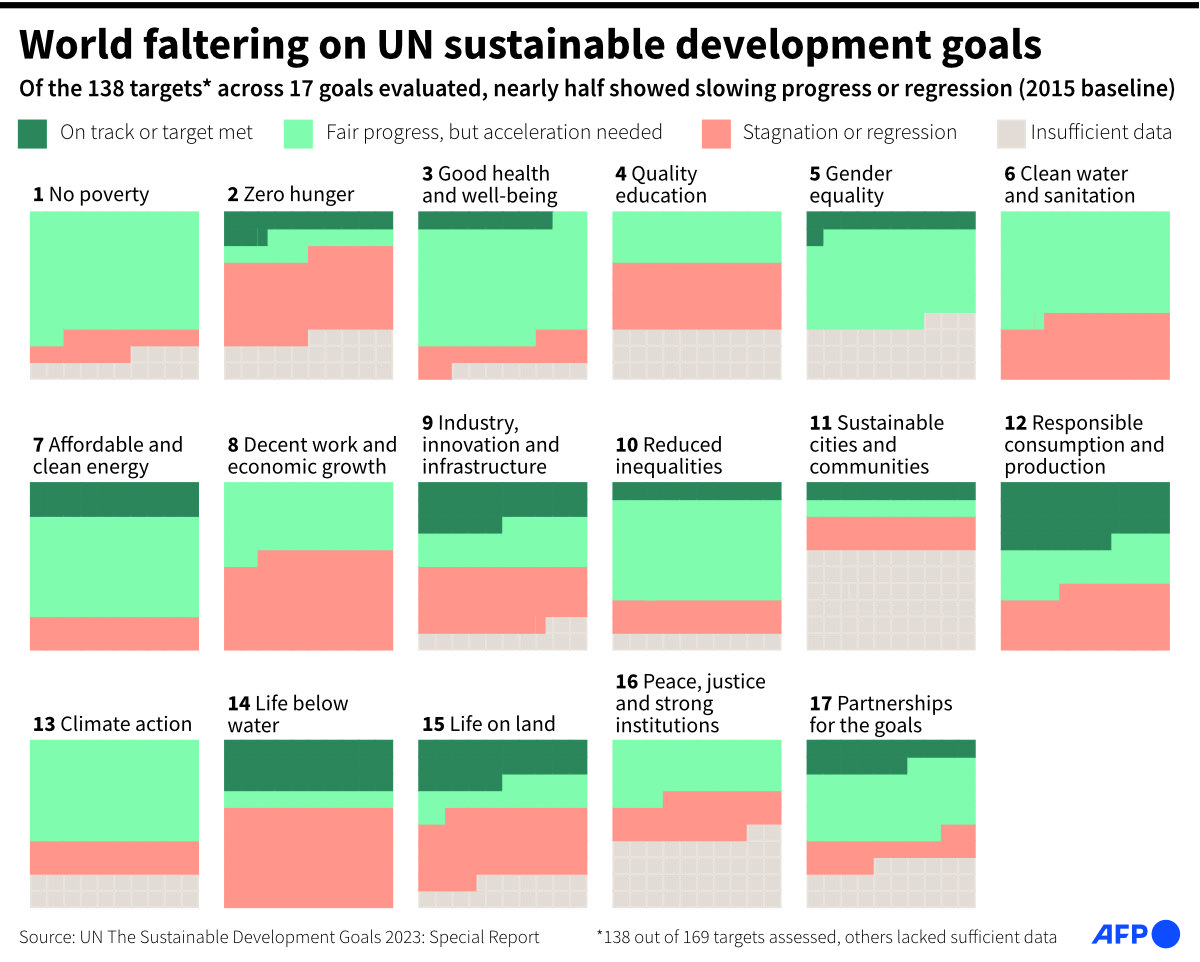

“Obviously when states, when international community agencies such as the UN, fail to protect people’s lives, when they fail to take control and to punish those who commit crimes, people will feel that they need to take things into their own hands,” said Al-Tikriti.

“And they will raise the volume of their narratives, the tone of their narratives, in order to expose the failures in the international community.

“The other side will call this extremist. The government might also call it extremist. The head of UK counterterrorism policing might also call it extremist. I just call it a natural human reaction.”

For Mendoza, the international community’s response is likely immaterial in the eyes of extremist groups. “Extremists will use whatever factor they can to further their narratives,” he said.

“If the dial is not turned on Middle East peace, they will use that as a path to recruiting for justice. And yet if the dial is turned, they will reject the peace deal that emerges as a betrayal of the historic land of Palestine and use that instead.

“Equally, whether there is or isn’t further conflict in the Middle East, the situation will be spun to their benefit. This reminds us that the real problem of radicalization is not a foreign policy issue but a domestic policy.

“If extremists are given free rein to organize and push their propaganda, then they will reap the rewards. It is only by adopting a zero-tolerance approach to their fantasies that we will be able to put the genie of radicalization back into its bottle.”

Regardless of how extremist groups may manipulate the narrative, the figures published by UK counterterrorism authorities show a correlation between the conflict in the Middle East and increased radicalization, creating a potential security threat.

“Extremist narratives resonate because they always contain some kernels of truth,” said Pearson. “The longer a conflict goes on, the more violence and injustice is visible online that bolsters the narrative, the greater the ongoing risk.”