Daesh changed the terms of the debate on extremism

Summary

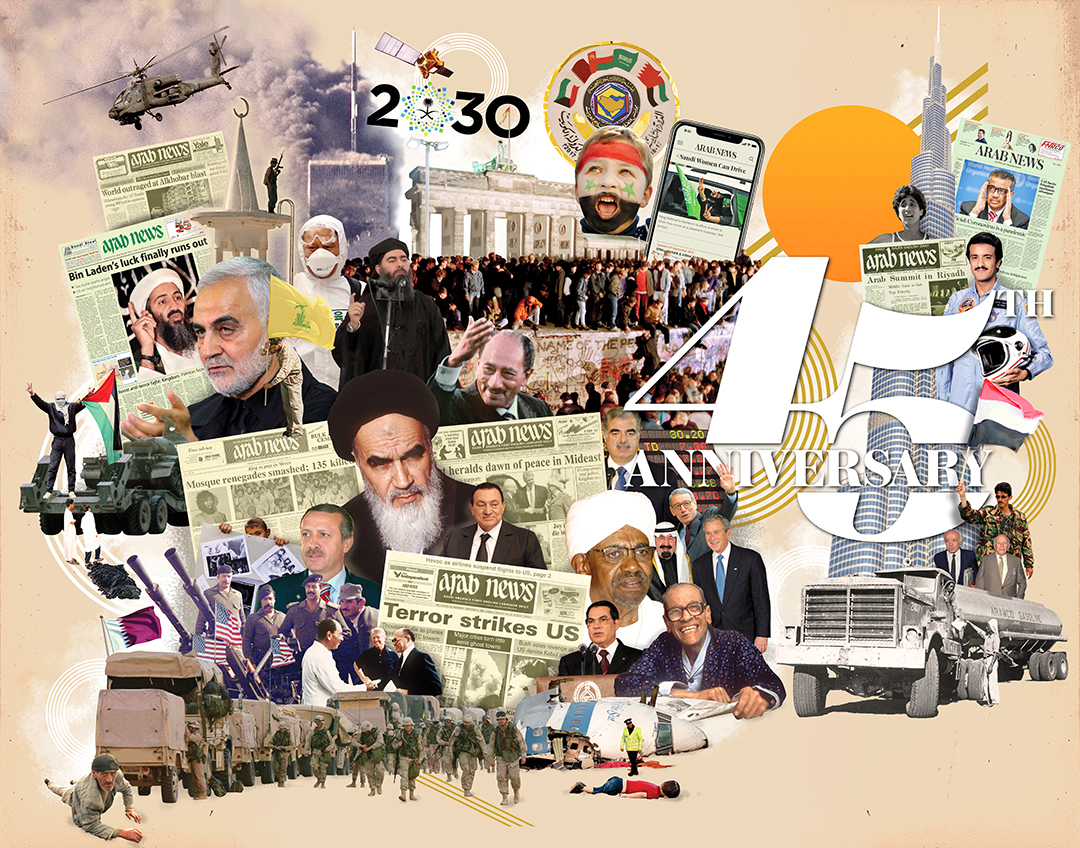

On June 30, 2014, Arab News reported that a Sunni terrorist group, the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, had declared the formation of a caliphate, imposing its extreme interpretation of Shariah law on areas it had conquered in Syria and Iraq.

Led by Iraqi-born “caliph” Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, it declared it would henceforth be known only as the Islamic State, a caliphate whose territory extended from Aleppo in Syria to Diyala in Iraq.

Known in the Arab world as Daesh, the organization was responsible for a reign of terror in which thousands were killed or held as slaves, priceless antiquities were destroyed or stolen, and historic sites from Palmyra in Syria to Mosul in Iraq were devastated.

Although Daesh continues as an ideological threat, over the past five years a US-led coalition of dozens of nations, including all six Gulf Cooperation Council states, has stripped it of the 110,000 square kilometers of territory it once controlled, liberating 7 million people.

In October 2019, Al-Baghdadi committed suicide during a US raid on his hideout in northern Syria.

In June 2014, I was part of the team that launched a new think tank looking at religious extremism. Our patron, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, had long been concerned that the ideological element of extremist groups was being overlooked, and it needed more policy-focused research.

That month, Daesh raced through northern Iraq, routing government troops and capturing a vast quantity of material that would strengthen its new position. On June 29, in the central mosque in Mosul, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, the group’s leader, declared himself to be caliph of a new caliphate.

The world was fascinated and horrified. Most had never heard of Daesh, or were aware of its links to Al-Qaeda in Iraq during the Iraq War. How had this group come out of nowhere to conquer the north of Iraq in addition to its territories in Syria? Interest was such that an article I published on our think tank’s website explaining where the group had come from was at one stage the top result in Google searches.

For extremists and their sympathizers across the world, this was the moment they had been waiting and fighting for over many years. Al-Qaeda’s softly-softly approach had caused immense frustrations; here at last, they thought, was a leader and a group capable of delivering on what it promised. Extremists flocked to Daesh in their droves; estimates in 2016 put the number of foreign fighters who had joined at 40,000, with a flow at its peak of up to 2,000 per month. The majority of these foreign fighters were from the Middle East and North Africa, but they included a large number from the West, and South and Southeast Asia too.

Throughout modern history, in every kind of social or political movement, new kinds of organizations have emerged and changed the terms of the debate. Al-Qaeda did that with the 9/11 attacks. Daesh did the same in 2014.

All across the globe, people still claim to be acting in the name of Al-Baghdadi’s supposed caliphate

Peter Welby

Daesh’s use of propaganda probably received the most focus (and parts of its violence, such as the immolation of Muath Al-Kasasbeh, the Jordanian pilot, were for propaganda purposes). It produced slick videos and professionally edited and produced magazines. It created vast networks on social media. Counter-Daesh efforts sought to emulate this, with very limited success, because the majority of efforts seemed unable to grasp that the production of slick videos was not the point, but merely a mechanism for communicating the point.

Key Dates

-

1Daesh declares the formation of a caliphate, led by Iraqi Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Al-Badri, aka Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi.

-

2Al-Baghdadi makes his only known public appearance, in a video filmed at the Al-Nuri Mosque in Mosul.

-

3Daesh posts photographs of the beheading of dozens of captured Syrian soldiers. Over the next year, more filmed beheadings would follow, including those of US journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff and British aid workers Alan Henning and David Haines.

-

4The Global Coalition Against Daesh is formed by the US.

-

5Daesh fighters murder 163 people in Mosul, Iraq.

-

6Daesh destroys the historic Great Mosque of Al-Nuri in Mosul.

-

7Daesh destroys monuments at Syria’s UNESCO World Heritage site at Palmyra.

-

8US Special Forces track Al-Baghdadi to a hideout in northern Syria, where he kills himself and three children by detonating a suicide vest.

-

9At a ministerial meeting in Washington, the 82-member global coalition celebrates the liberation of the group’s former territories but warns “these achievements and Daesh’s enduring defeat are threatened... our work is not done.”

Another area of total change was in Daesh’s approach to governance. Other transnational terrorist groups had attempted governance before — notably Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in the aftermath of 2011. And other extremist groups of different ideological stripes had tried it on a large scale, such as the Taliban in Afghanistan. But Daesh was the first group with an explicitly transnational ideology (it sought to establish a global caliphate) to attempt governance at scale. It put out calls to doctors and teachers; it announced the launch of a currency with great fanfare; it encouraged those who traveled to its territory to burn their passports.

Iraq said Daesh’s ‘caliphate’ was coming to an end three years to the day after it was proclaimed, following the recapture of Mosul’s iconic Al-Nuri Mosque on Thursday.

From a story by Siraj Wahab on Arab News’ front page, June 30, 2017

This relates to the third area of total change, and the reason that, even now, with the majority of Daesh territory liberated, extremists all over the world are still carrying out attacks in the group’s name. Daesh’s actions in 2014 had proclaimed a message across the Islamist world: “We Deliver.” For decades, different groups had been claiming to seek a caliphate. Most observers laughed at this fantasy and focused on how the West, in their eyes, could stop provoking such groups. Daesh’s actions granted it legitimacy in the sight of its ideological sympathizers. Fighters for other extremist groups in Syria and Iraq defected — in contrast to Daesh, their leaders were mere warlords. Groups from Nigeria to the Philippines swore allegiance. And, right across the Middle East and North Africa, Daesh cells claimed to expand its jurisdiction.

Wind forward nearly six years and Al-Baghdadi is dead, while the territories he commanded across Syria and Iraq are Daesh territories no more. But the allegiance to the idea has remained: In Nigeria, the Sinai, Yemen, Syria, Iraq and elsewhere across the globe, people still claim to be acting in the name of Al-Baghdadi’s supposed caliphate.

A page from the Arab News archive showing the news on June 30, 2017.

This is the power of ideology. When we focus on personalities, propaganda or territory, we risk missing the most important aspect. It was not Al-Baghdadi’s charismatic personality that drew people who had never met him and hardly ever heard him speak to pledge allegiance. If slick films were enough, the world would be rushing to pledge allegiance to Peter Jackson. If territory were the key, then support for Daesh’s would have dried up on the banks of the Euphrates. All of these things are important, but it is the idea of the caliphate, and the means to achieve it, which holds Daesh’s supporters together.

- Peter Welby is a consultant on religion and global affairs, specializing in the Arab world. Previously he was the managing editor of a think tank on religious extremism, the Centre on Religion & Geopolitics, and worked in public affairs in the Arabian Gulf. He is based in London, and has lived in Egypt and Yemen. Twitter: @pdcwelby